Preamble

In a landscape where people and organizations are under pressure to innovate, deliver value, and remain adaptable, the adoption of frameworks, methodologies, and processes has become central to strategy and execution. Yet despite their ubiquity, many individuals and teams struggle to grasp these constructs, differentiate their roles, or implement them effectively. The confusion is not trivial—it impacts project outcomes, stakeholder alignment, and organizational maturity. It causes adoption fatigue for users, an example is the adoption of software engineering frameworks from Waterfall to Agile. Success rate is measured by delivery on time and within budget has been abysmal . Frameworks, Methodologies, and Processes; understanding, implementation, organisation learning curve and churn, has been identified as a significant factor, impacting delivery for large scale projects. (lets not forget historic death by documentation and now it is little or no documentation).

This article distils the essence (outline) of a comprehensive guide that maps out clear definitions, hierarchical relationships, domain-specific adaptations, and implementation pathways. It offers a lens through which professionals—from product managers to UX designers, engineers to educators—can better understand the tools at their disposal. More importantly, it provides a structured approach to contextualising and operationalising them within unique organizational environments. Whether you are introducing Agile to a design team or tailoring a compliance-driven framework in healthcare, the challenge is not just adoption—it is making meaning.

The big question what are Frameworks, Methodologies, and Processes in detail: The comprehensive Guide to Frameworks, Methodologies and Processes . Please review analyse and critique.

A1. Foundational Definitions and Conceptual Framework (Summary)

A1.1 Core Definitions

Framework

- A high-level, structured conceptual model that provides overarching guidance, components, Body of knowledge \Best practice (non -prescriptive) , Templates, Visual models, Reference models and relationship mappings (ideally referencing inspiration, concepts, research, analysis, academic or case study, scope, domain or guiderails etc)

- Characteristics: Flexible, adaptable, non-prescriptive, strategic-level

- Examples: BIZBOK (Business Architecture), BABOK (Business Analysis), TOGAF (Enterprise Architecture), SAFe (Scaled Agile), ISO 27001 (Information Security)

Methodology

- A systematic, coherent set of methods, rules, and procedures designed to guide specific activities or projects. (ideally referencing a Body of Knowledge (BOK), or Framework, research , analysis, scope, domain or guiderails etc )

- Characteristics: Semi-prescriptive, context-driven, tactical-level, with defined phases

- Examples: Scrum, Design Thinking, , Waterfall, Lean Start-up

Process

- A defined sequence of interconnected tasks, activities, and decision points designed to achieve specific, measurable outcomes (ideally referencing a methodology, Guidelines, scope, domain or guiderails etc )

- Characteristics: Highly prescriptive, repeatable, operational-level, with clear inputs/outputs

- Examples: Requirements gathering → Analysis → Design → Development →Testing → Implementation

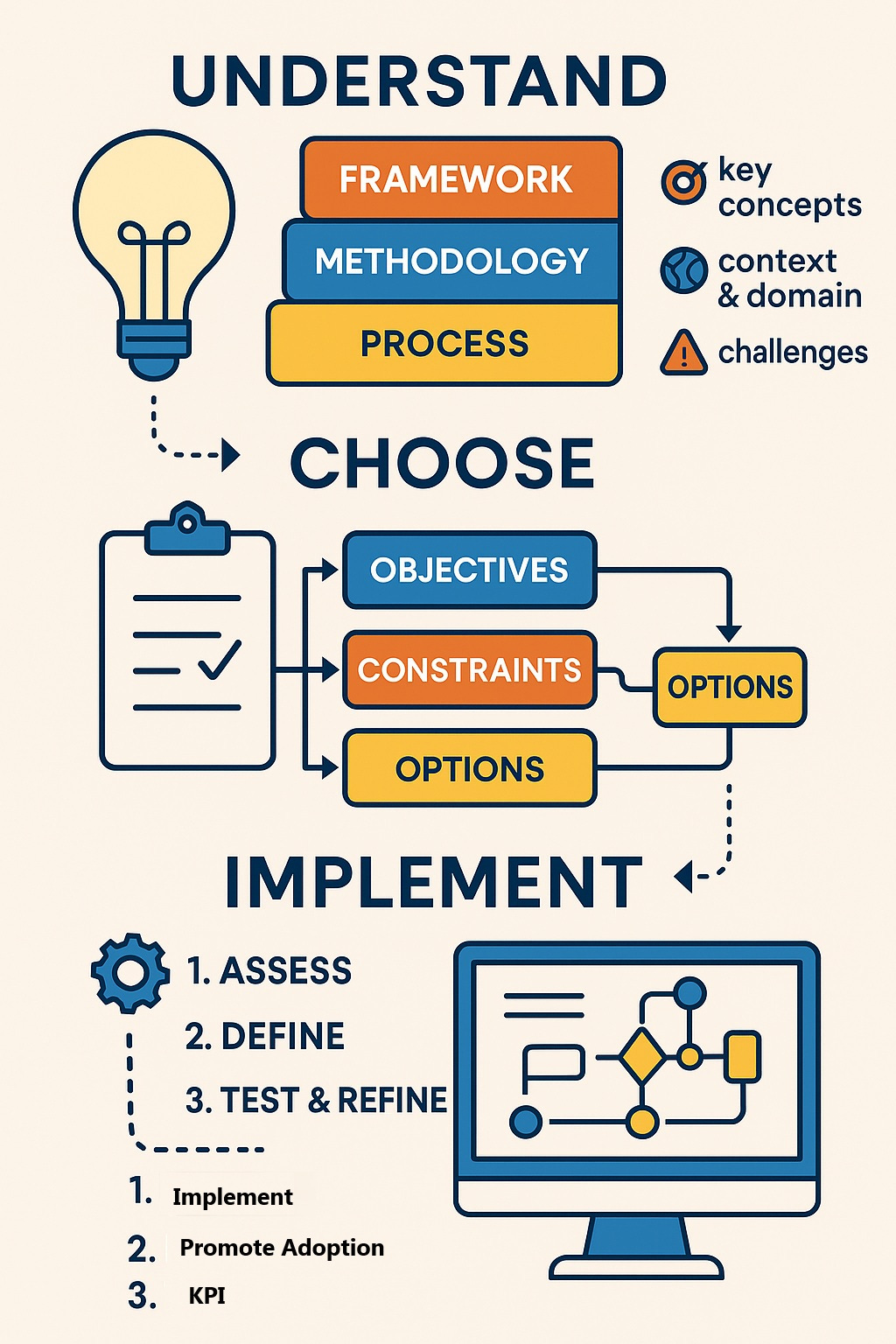

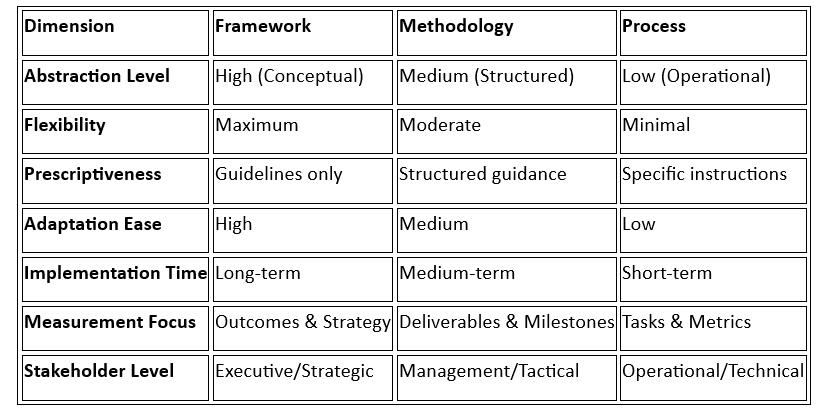

A1.2 Hierarchical Relationship Model

STRATEGIC LEVEL → Framework (What scope and why)

TACTICAL LEVEL → Methodology (How to approach)

OPERATIONAL LEVEL → Process (What specific steps)

A1.3 Domain

The term domain generally refers to a specific area of knowledge, expertise, or activity. It’s a context or sphere within which certain rules, practices, and language apply: Industry (sector) Domain, Knowledge Domain, Scientific, Technical or Digital Domain, Problem Domain vs. Solution Domain etc. A singular domain with a scope is usually a starting point but in application there could be cross domains, hybrid domains, multiple domains, leading to a framework that explains everything based on a theory (or hypothesis) of everything (see what I did with the hypothesis thing? Here is an Easter Egg).

A2. Comparative Analysis Matrix

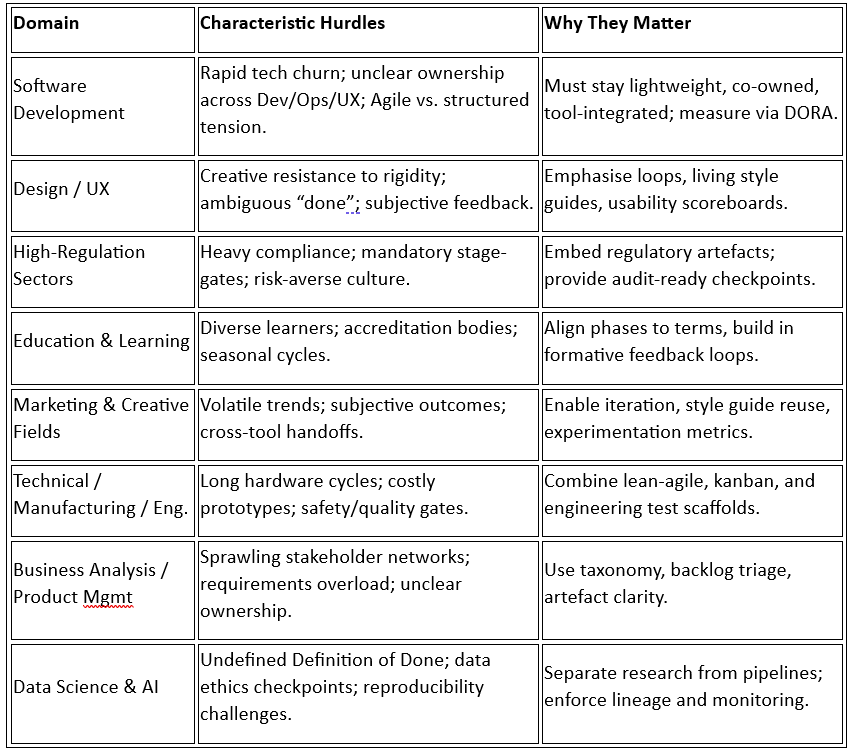

A2.1 Domain-Specific Analysis and Applications

Business Analysis Domain (example)

Frameworks:

- BABOK (Business Analysis Body of Knowledge)

- IIBA Standards

- Agile Business Analysis Framework

- Rational Unified Process (RUP) mistakenly named a process

Methodologies:

- Agile Business Analysis

- Waterfall Business Analysis

- Lean Business Analysis

- Requirements Engineering

Processes:

- Stakeholder identification and analysis

- Requirements elicitation and documentation

- Gap analysis execution

- User story creation and validation

- Business case development

Domain Adaptability Factors:

- Organizational maturity level

- Project complexity and scale

- Regulatory environment

- Stakeholder diversity and geographic distribution

A2.2 Example: I have created a sample case study in the Appendices

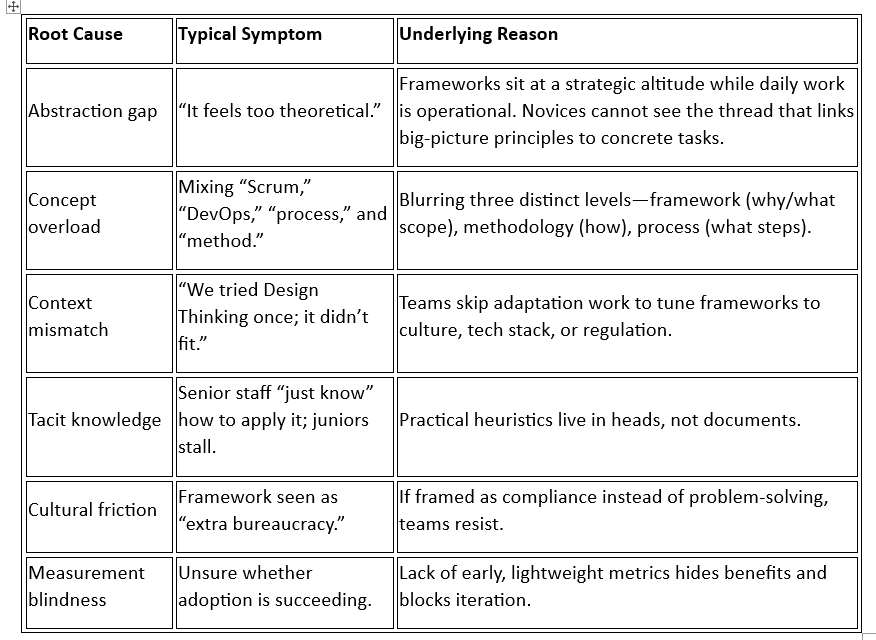

We have all used these terms interchangeably and we will debate it and critique it. It is noteworthy that definitions of words and meanings might change when applied to different domains (industry, business type, subject matter). Even within a domain there are contentions for example in the Agile domain, I think that SCRUM is a methodology based on the Agile Framework or Agile body of knowledge. I have been roasted in discussions and actually hissed at in a meeting and then I realised that there are issues of ; shared Definitions, Domain, level of Abstraction or Hierarchy, Authority (credibility) , Authorship (source) , and Adoption (and or Experience).

1. Why People Struggle to Understand, Conceptualise & Apply Frameworks / Methodologies / Processes

2. Domain-Specific Hurdles

3. Business Architect, Analyst or Researcher’s Playbook for Analysing a New Framework

- Locate its level: framework, methodology, or process.

- Break it down: principles, roles, artefacts, ceremonies.

- Mark what’s fixed vs. adaptable.

- Draw value flow (e.g., SIPOC diagram).

- Identify metrics it aims to move.

- Compare against current workflows using a gap analysis.

- Research existing Frameworks and related implementation playbooks (Example Business Architectural Guild: Concepts (body of knowledge), frameworks, templates, examples and reference models)

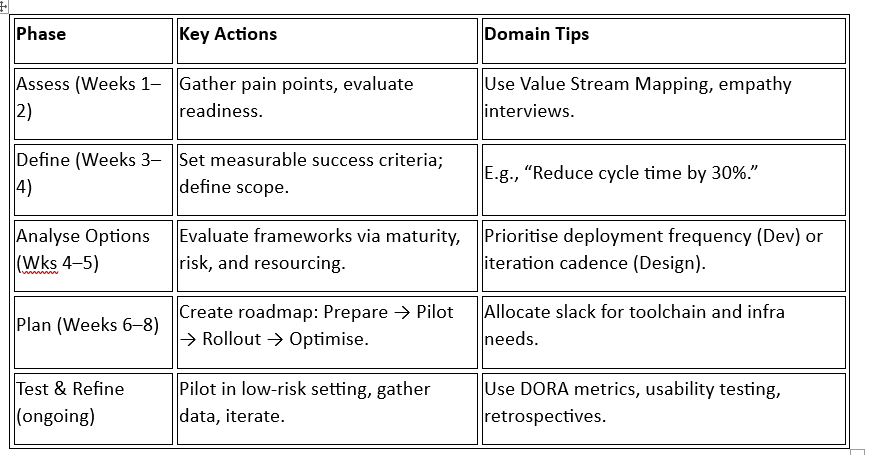

4. Structured Adaptation & Implementation Approach

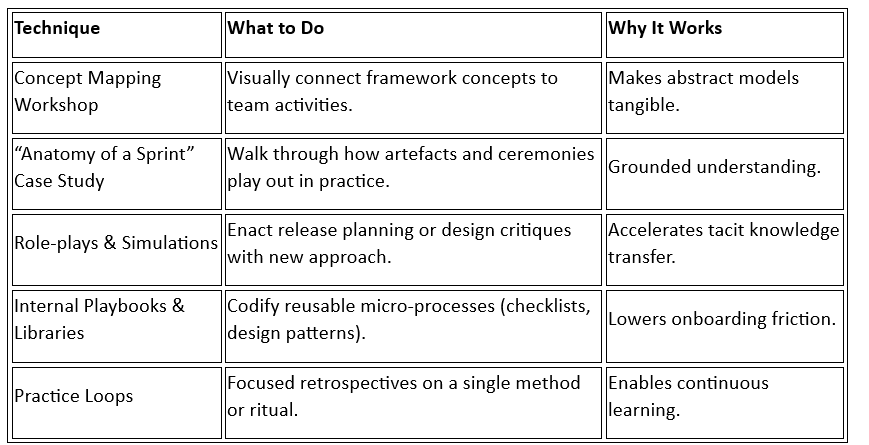

5. Tactics to Boost Understanding

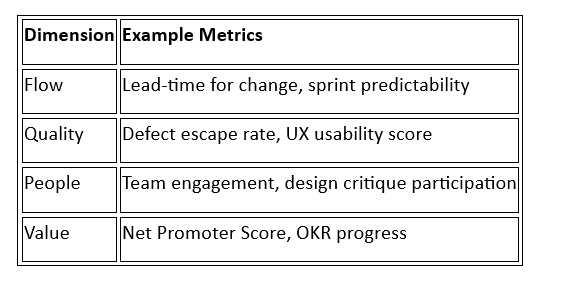

6. Measurement & Feedback Essentials

Begin tracking from Day 0 — what gets measured improves.

Review metrics bi-weekly; adjust not only targets, but also the working methods.

7. Key Takeaways for Researchers & Analysts

- Clarify altitude: Identify if it’s a framework, methodology, or process before critique or rollout.

- Treat adaptation as a project: Context-fit is the single greatest success driver.

- Use sense-making rituals: Concept maps, case studies, and lived playbooks embed new patterns.

- Close the loop with metrics: Use data to support adoption, not just performance.

Conclusion

Successfully navigating the landscape of frameworks, methodologies, and processes is less about blind adoption and more about contextual understanding and intentional design. Organizations and professionals must move beyond surface-level familiarity and engage deeply with the purpose, structure, and application of these tools. By distinguishing clearly between strategic frameworks, tactical methodologies, and operational processes, teams can unlock more precise decision-making, smoother collaboration, and more meaningful outcomes.

This guide reinforces that no one-size-fits-all model exists. Instead, the path to effective implementation lies in thoughtful adaptation—anchored in domain realities, team dynamics, and measurable impact. For researchers, analysts, and practitioners alike, the imperative is clear: understand the altitude, tailor the fit, and measure what matters. Only then can frameworks stop being theoretical overlays and start becoming living systems of value creation.

Appendices

Case Study: Embedding a Framework, Methodology, and Process for AI-Enabled Software Development in a Large Enterprise

Context

In early 2024, a global financial services organisation initiated a multi-year transformation programme aimed at modernising its technology stack and accelerating delivery. While various teams had begun experimenting with artificial intelligence (AI) tools—ranging from data modelling assistants to automated test generators—there was no unified approach to integrating these capabilities into core software development practices.

Complicating matters were three parallel realities:

- A portfolio of legacy systems built on mainframes and bespoke middleware,

- A stream of in-flight development projects using varying degrees of agile delivery, and

- A backlog of net-new digital products expected to be AI-enabled by default.

A clear architectural and operational response was needed—one that could integrate AI responsibly and effectively across the entire software development value chain.

Stakeholder: The Business architect introducing a structured framework, methodology, and process for AI-enabled software development in a large organisation.

Objective

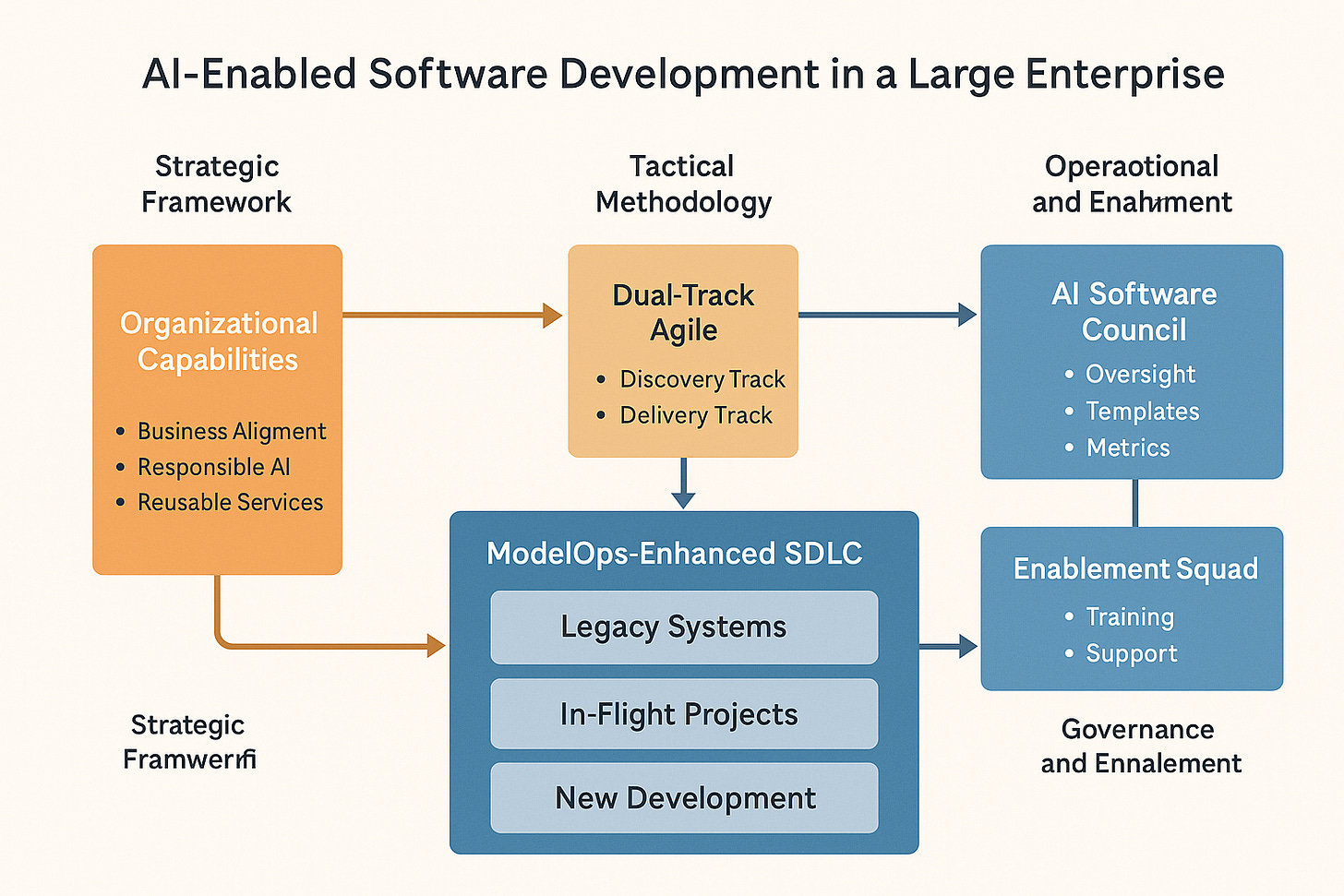

To introduce a structured and scalable approach—comprising a framework (strategic), a methodology (tactical), and a process (operational)—to enable AI-supported software development across legacy modernisation, work-in-progress (WIP) builds, and greenfield development.

Strategic Framework: Capability-Led Value Streams

We anchored the effort in a Capability-Led Framework. This involved:

- Mapping technology and delivery functions to business capabilities, ensuring AI adoption supported core value streams (e.g., underwriting, claims processing, risk analytics).

- Positioning AI as a horizontal enabler, not a vertical product. This avoided siloed AI experimentation and promoted shared services for data, models, and inference tooling.

- Establishing guardrails for responsible AI, including explainability, data provenance, and auditability. These principles were codified into enterprise architecture artefacts.

- Evangelising the new approach to get buy-in, adoption (and deal with change fatigue) and implementation.

This strategic framework ensured alignment between business objectives and AI integration, regardless of where development occurred in the portfolio.

Tactical Methodology: Dual-Track Agile with AI Integration

To support cross-cutting delivery, we tailored a Dual-Track Agile methodology to include specific guidance for AI use. Key adaptations included:

- Discovery Track:

- Technical feasibility assessments including data readiness and ML applicability.

- AI-specific user stories (e.g., “As a claims handler, I want the model to explain confidence levels…”).

- Model architecture design treated as a first-class deliverable.

- Delivery Track:

- Integration of model development pipelines into DevOps.

- Parallel “AI Assurance” ceremonies covering fairness testing, regression detection, and drift monitoring.

- Continuous retraining cycles aligned to sprint cadence.

Importantly, this methodology worked alongside existing scrum or SAFe teams, preserving local team autonomy while introducing clear structure for AI-specific tasks.

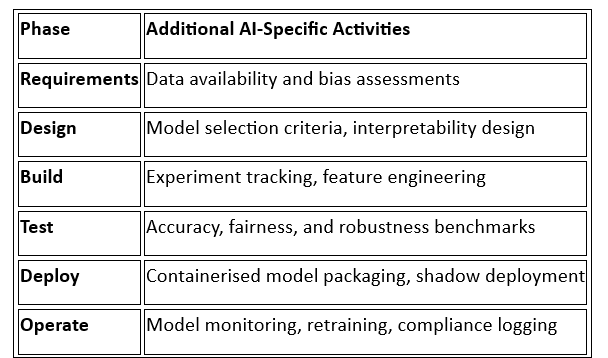

Operational Process: ModelOps-Enhanced SDLC

At the process level, we designed a ModelOps-enhanced Software Development Lifecycle (SDLC) that introduced new steps without overwhelming existing teams:

Legacy system teams applied this process selectively—for example, introducing model-driven code remediation tools. New product teams used it end-to-end, building real-time decisioning into apps from day one.

Governance and Enablement

We established an AI Software Council composed of architecture, product, compliance, and engineering leaders. This group:

- Reviewed early pilots for alignment and risk exposure,

- Curated reusable components (e.g., a pre-trained document classifier),

- Managed updates to playbooks, templates, and success metrics.

Additionally, an Enablement Squad supported adoption through:

- “AI in Dev” clinics with hands-on help for teams,

- Inclusion of AI literacy in onboarding and developer academies,

- A shared knowledge portal with annotated examples and reusable pipelines.

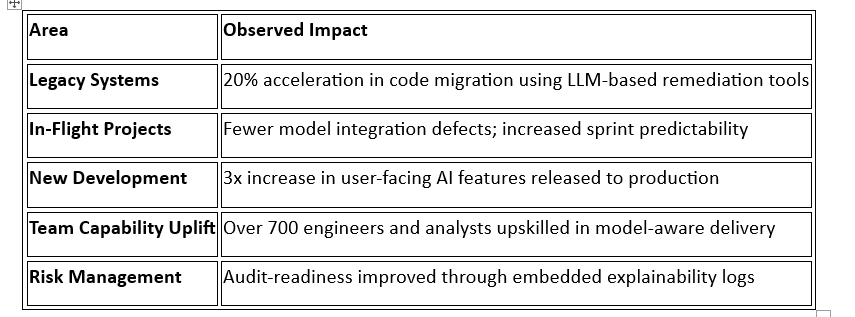

Outcomes After Six Months

Lessons Learned

- Start with business capability—not technology appetite. This kept AI grounded in value, not novelty.

- Treat AI as a team member, not a magic box. Integrating tools into ceremonies helped demystify usage.

- Respect the pace layers. Legacy, WIP, and greenfield teams each needed tailored entry points—not a single-speed rollout.

- Measurement drives trust. Early visibility into outcomes built the case for scale-up.

- Focus on being process and tech agnostic at initiation: to establish Pain points, Business case and AI Impact, implementation and Cost \Benefit business advantage.

Next Steps

The enterprise is now scaling the approach across three additional regions and embedding ModelOps into vendor procurement guidelines. A new “AI Engineering Centre of Excellence” is being stood up to maintain cohesion as tooling, platforms, and regulations evolve.