Preamble

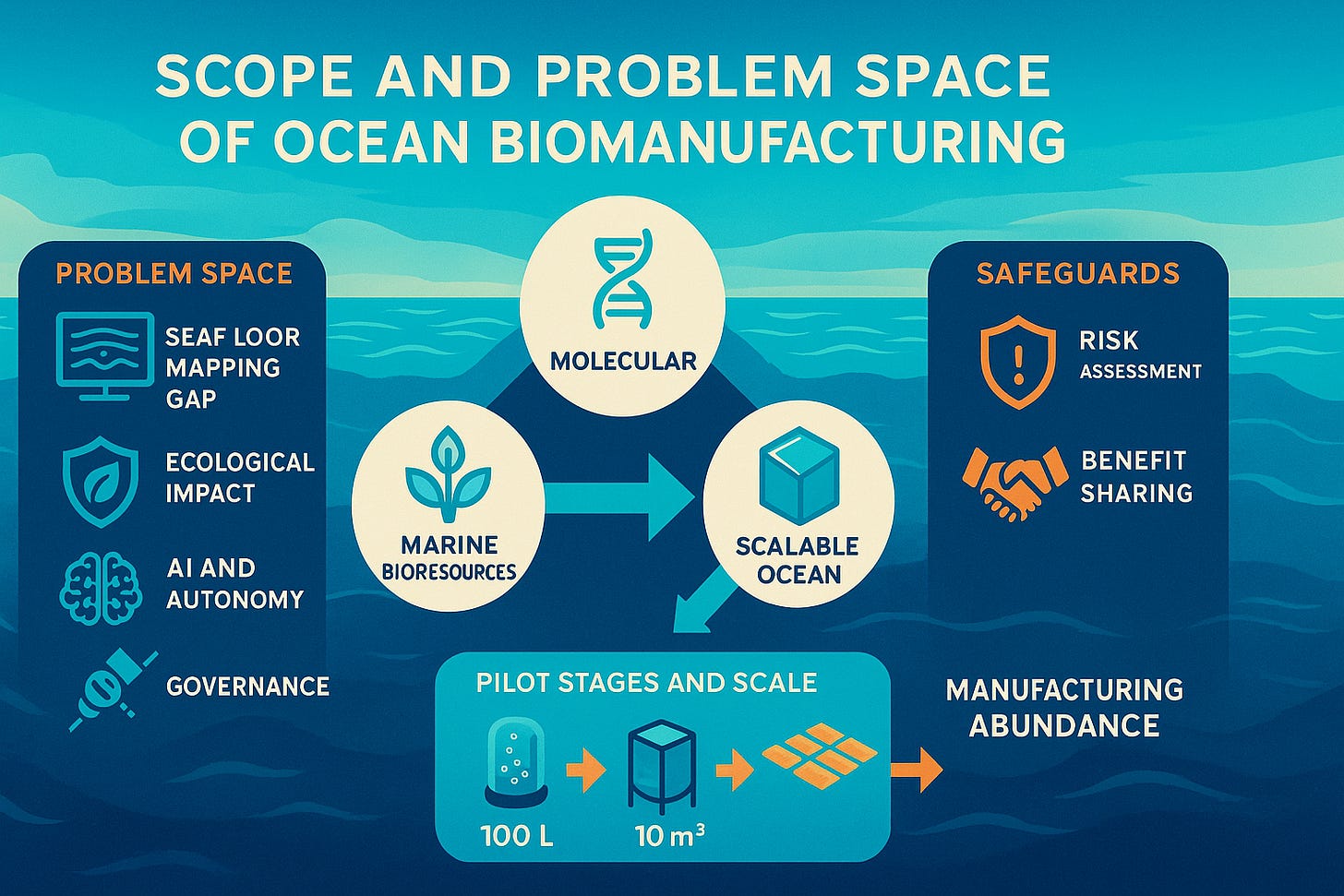

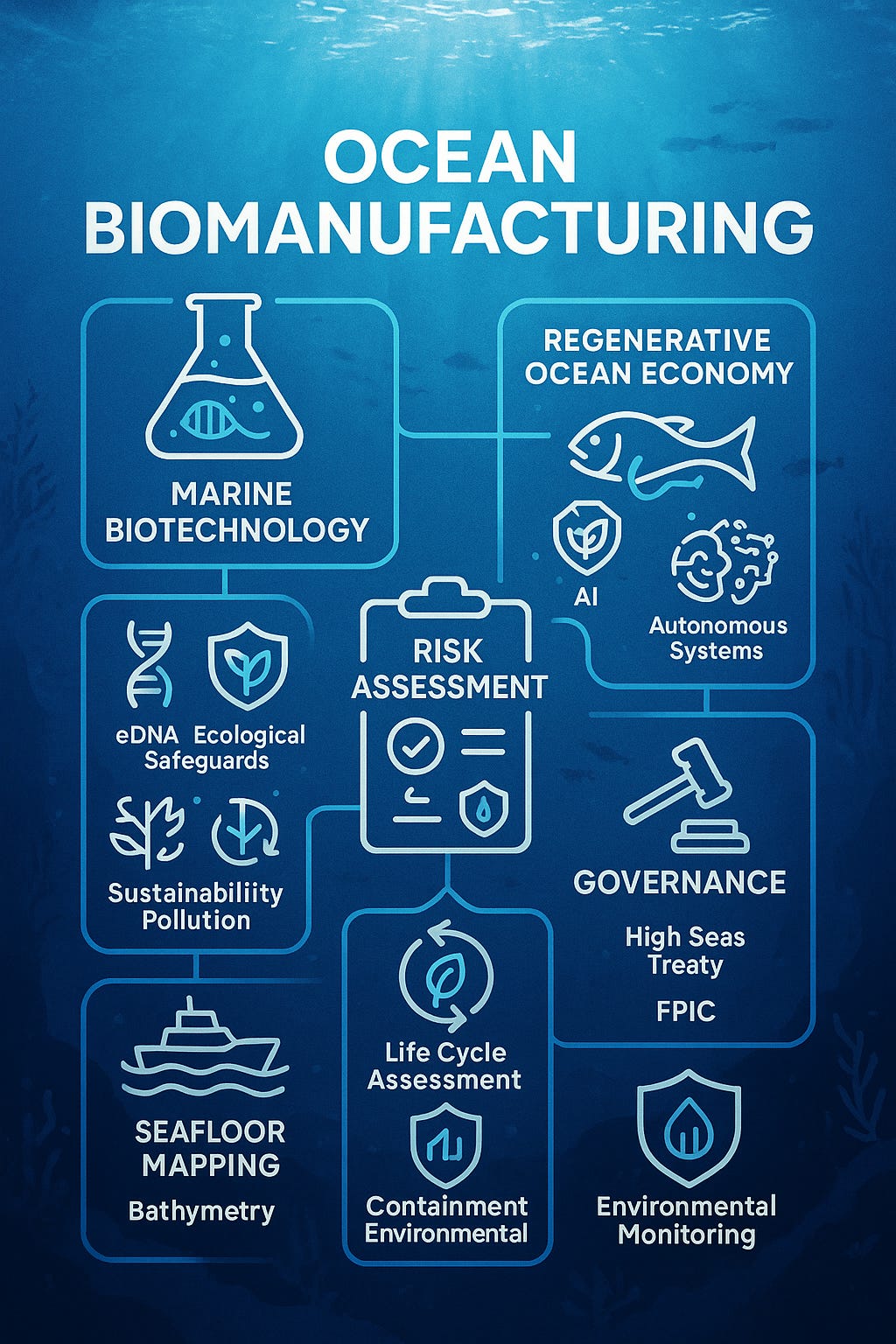

Two emerging areas Emerging areas caught my attention at ARIA. I already shared a contribution on the Collective Intelligence Engine I think my post The Foresight Nexus: An advanced Human-AI Inference and extrapolation Application and Framework addresses most of this and I sent them my contribution. The second area is Ocean Biomanufacturing. I prepared an outline analysis that treats ocean systems as living ecosystems, not extractive reservoirs. Success must be measured by ecosystem health, the wellbeing of ocean communities, and the condition of the oceans we pass on. when considering Ocean Biomanufacturing which represents a different concept from extractive to regenerative relationships with the ocean. It recognizes that the ocean is not merely a resource to be exploited, but a complex, living system deserving of respect, protection, and enhancement. The approach that prioritizes the health of marine ecosystems and the rights of all ocean stakeholders, should create a model for sustainable development that future generations can build upon. Success will be measured not by economic returns alone, but by the health of marine ecosystems, the wellbeing of ocean-dependent communities, and the condition of the oceans we leave for future generations. I am sure ARIA are looking at the science and technology aspects of Ocean Biomanufacturing and this is my contextualisation Scope: Ocean Bioengineering as a Problem space

Introduction

What is marine Bio Engineering and its current status

Marine bioengineering (also called marine biotechnology) is the creation of products and processes from marine organisms through the application of biotechnology, molecular and cell biology, and bioinformatics Marine Biotechnology | ISAAA.org. It’s an interdisciplinary field that uses the latest breakthroughs in modern molecular biology, engineering and chemistry to solve basic problems in marine biology; to improve the production of medical, chemical, food, and energy resources from the ocean; and to develop new products and industries based on more efficient use of the ocean’s resources Biotechnology and Engineering | UCSB Marine Science Institute.

Key Applications

Marine bioengineering spans multiple industries and applications:

Biomedicine and Pharmaceuticals: The marine environment provides unique compounds for drug discovery. The marine environment is the most biologically and chemically diverse habitat on Earth, and provides numerous marine-derived products, including enzymes and molecules, for industrial and pharmaceutical applications Recent advances in biotechnology for marine enzymes and molecules – PubMed.

Aquaculture and Food Production: Engineering better methods for marine farming and sustainable seafood production.

Bioenergy: Developing algal biofuels and other renewable energy sources from marine organisms.

Environmental Applications: Using marine biotechnology for pollution control, ecosystem restoration, and addressing environmental challenges.

Industrial Biotechnology: Marine biotechnology applications are essentially diverse and numerous, as evidenced by the fact that it is currently utilised across different industries, such as the aquaculture, biomedical, pharmaceutical, bioplastics, and alternative energy sources sectors Exploring the Applications of Marine Biotechnology in Ocean Conservation.

Marine Biotechnology vs Deep Sea Mining (See: Definition differences and similarities)

Definitions

- Marine bioengineering. The use of marine organisms, genes, enzymes, and ecosystems to design processes or products, such as materials, chemicals, medicines, sensing, or bioremediation. It includes sea based bioprocessing, engineered consortia, and algae cultivation.

- Deep sea mining. The industrial extraction of minerals from the seabed, typically polymetallic nodules, seafloor massive sulfides, or cobalt crusts, using collectors, riser systems, and support vessels at depths of hundreds to thousands of meters.

Marine bioengineering and deep sea mining both operate offshore with advanced sensors, robotics, and strict logistics, but they pursue very different goals and carry different risks. Marine bioengineering uses organisms, genes, and enzymes to make materials, chemicals, and services, often with modular platforms that can be paused, removed, and monitored in real time. Its main risks are genetic escape, releases, and interactions with wild species, which you can manage with multi barrier containment, ecological triggers, and open data. Deep sea mining extracts metals from nodules, crusts, or sulfides and creates large, hard to reverse disturbances on the seabed, with sediment plumes, noise, and slow recovery. Both require strong baselines, continuous monitoring, and rigorous EIAs, and both face questions of who benefits, who bears risk, and how to prove safety. A simple test for decision makers is to ask if the activity is reversible at the site scale, if automatic shutdowns are proven and funded, if rightsholders have consent and fair benefits, if environmental data are public and audited, and if the option delivers greater public value than alternatives.

Current Status of marine Biotechnology

The field has experienced significant growth and development:

Market Growth: The Marine Biotechnology Market accounted for USD 6.95 Billion in 2024 and USD 7.47 Billion in 2025 is expected to reach USD 15.4 Billion by 2035, growing at a CAGR of around 7.50% between 2025 and 2035 Marine Biotechnology Market Share, Size & Growth 2025-2035.

Research Momentum: Modern marine biotechnology has been developing rapidly since the 1980s. There are promising and exciting achievements in biochemistry, genetics, genomics, aquaculture, bioenergy, and other related fields, beginning with genetic recombinant technology as applied to marine algae Marine Biotechnology – PMC.

Challenges and Opportunities: Despite its potential, marine biotechnology has not yet matured into an economically significant field. Fundamental knowledge is lacking in areas that are pivotal to the commercialization of biomedical products and to the commercial application of biotechnology to solve marine environmental problems Biomedical Applications of Marine Natural Products: Overview of the 2001 Workshop – Marine Biotechnology in the Twenty-First Century – NCBI Bookshelf.

The field continues to evolve rapidly, with recent advances focusing on marine biomolecules, sustainable ocean resource utilization, and addressing global challenges like climate change and food security through ocean-based solutions.

Why this outline analysis

I approach ocean biomanufacturing as a synthesis problem. We need a shared ethical, ecological, and operational framework that guides technology choices, siting, monitoring, and governance. I developed complementary frameworks to keep ecological integrity first, and to align with new global rules.

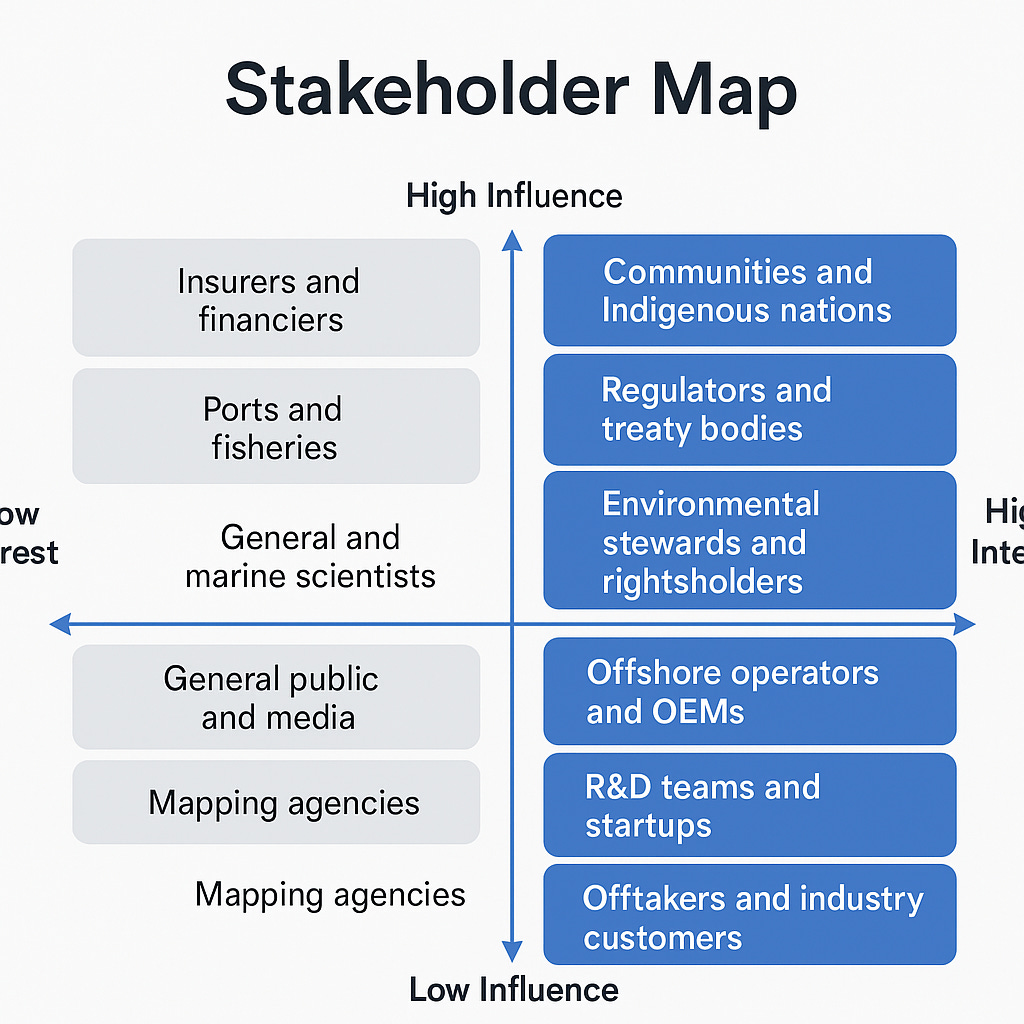

Stakeholder Analysis (see: Stakeholder Mapping)

Applications and early markets

- Biomedicine and specialty chemicals. Marine enzymes and molecules enable new therapeutics and processes.

- Food and aquaculture inputs. Seaweed and microalgae support low impact proteins and feed additives.

- Materials and fuels. Algae and macroalgae feed bioplastics and sustainable aviation fuel pilots. Policy bans on single use plastics create predictable pull.

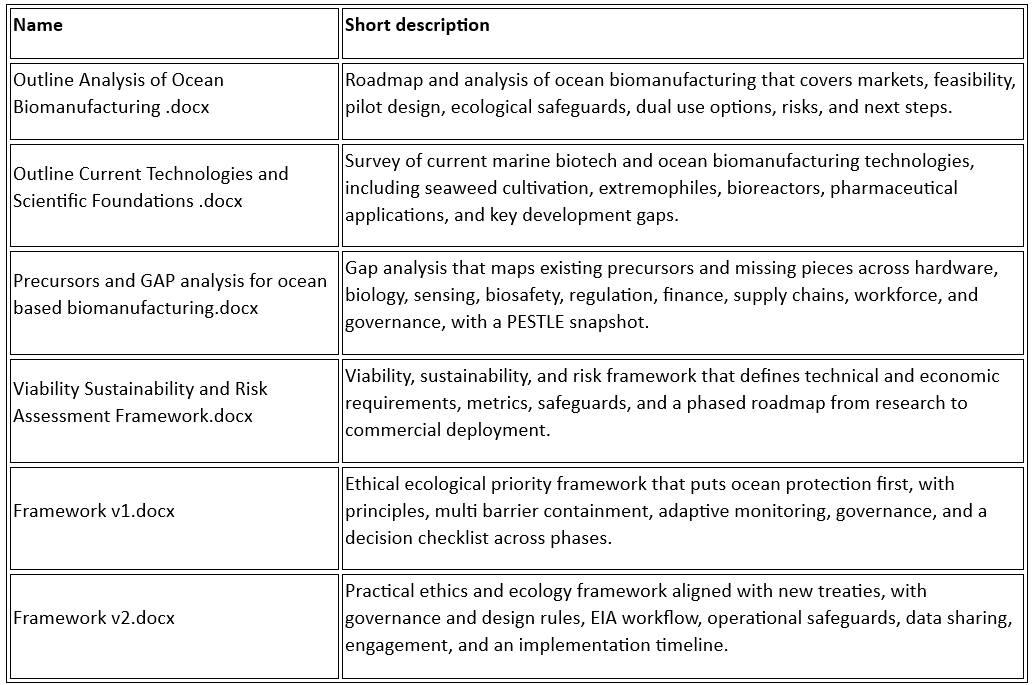

I created analysis artifacts : Analysis

Note: I created two documents (Framework 1&2) which present complementary but distinct versions of an ethical-ecological framework for ocean biomanufacturing and dual-use marine technologies. Both aim to ensure that industrial activity in the ocean enhances, rather than harms, marine ecosystems, while referencing justice, transparency, and collaboration.

Analysis of the Precursors for this industry (existing and missing)

Ocean biomanufacturing can borrow from offshore wind, aquaculture, ISO 14001 systems, and digital manufacturing. The largest gaps are salt tolerant biocatalysts, multi barrier containment that survives storms, real time eDNA dashboards, treaty aligned impact standards, and finance and insurance that price ecological risk. Workforce pipelines and enforceable benefit sharing also lag. Use this gap list to focus R&D, standards, and partnerships. Consider the gap that compares ocean biomanufacturing to mature industries, showing where strong precursors already exist and where critical pieces are still missing across hardware, biology, sensing, containment, regulation, finance, logistics, skills, social license, adaptive management, and global coordination. Apply a PESTLE lens to list current political, economic, social, technological, legal, and environmental building blocks alongside the biggest unresolved gaps, giving you a clear agenda for advocacy, R&D focus, and standards development in the next phase of work.

Seafloor knowledge gaps and why mapping matters

Detailed seafloor mapping is still incomplete in many regions. You can close part of that gap while you build pilots. Fit uncrewed surface vessels with multibeam sonar and sub bottom profilers alongside nutrient and eDNA sensors. Saildrone’s Surveyor class has already delivered deep water surveys while avoiding ship emissions. MIT’s sparse aperture sonar shows how small surface craft can produce meter scale bathymetry at high coverage rates. Integrate these capabilities with your arrays to map seabed structure, locate hazards, and improve siting.

Action for pilots. Specify universal sensor ports and power taps on every module so you can swap in sonar, sampler, or camera payloads as mission goals change. Start data sharing agreements with national mapping programs early.

Ecological impact, sustainability, and pollution

Design for measurable net positive impact. Combine life cycle assessment, continuous monitoring, and strict triggers that pause operations when metrics deviate.

- Risks to manage. Genetic escape, chemical releases, habitat disruption, and noise or light effects. Use multi-layer containment, closed loop processing, and adaptive shutdowns tied to ecological thresholds.

- What to monitor. Water quality, biodiversity indices, eDNA signals, acoustic and light environments, and ecosystem functions such as primary productivity and nutrient cycling. Publish non-commercial data for transparency.

- Pollution reduction opportunities. Algal circuits can strip heavy metals and nutrients from sidestreams, and engineered strains can secrete PET degrading enzymes that work in seawater. Dedicate spare capacity to cleanup experiments during off cycle periods.

Build governance with real power for communities. Secure free, prior, and informed consent where customary waters or traditional knowledge are involved. Share benefits and data in ways that respect knowledge sovereignty.

AI, automation (incl Robotics and Drones), and enabling technologies

AI and digital twins can stabilize yields, reduce energy, and shrink operator load. Pair them with dense sensor networks and autonomous systems.

- Process intelligence. Use AI for strain selection, feed control, and failure prediction. Close the loop with real time eDNA, nutrients, and acoustic data.

- Robotics , Drone and autonomy. Use uncrewed vessels for inspection, mapping, and sample collection. Add modular ports so every raft can host extra sensors without retrofit.

- Materials and containment. Combine self-healing or antifouling materials with genetic safeguards such as kill switches and dependency circuits. Validate containment under storm conditions.

Governance, standards, and policy alignment

Align projects with emerging rules, including the High Seas Treaty and biodiversity targets. Set up an Ethics and Ecology Board with equal seats for scientists, local communities, regulators, and investors. Require board sign off at concept, pilot, and commercial stages. Publish environmental data and maintain a standby restoration fund.

At the system level, major gaps remain in international liability, offshore FPIC processes, standards for real time eDNA monitoring, and insurance products that cover ecological harm. Participate in standards building while designing to the strictest available guidance.

The need for Viability, Sustainability, and Risk Assessment : Create a framework for assessment and strategic analysis for evaluating the feasibility, environmental integrity, and long-term potential of ocean biomanufacturing systems. Examining technical, economic, and ecological factors needed to move from concept to commercial scale. Identifying current technology readiness, capital and operational cost expectations, and market opportunities, while outlining phased research and development priorities.

The need for a robust sustainability framework covering environmental indicators, social equity, and economic durability, alongside integrated safety protocols for ecosystem protection. How to assess critical risks, technical, environmental, regulatory, and social impact and mitigation strategies. Can we draw lessons from terrestrial industrialization.

Consider Implementation roadmap

Years 1 to 3, foundation. Establish governance, complete baseline ecological surveys, stand up open data pipelines, and lab scale systems. Lock in siting criteria and shutdown triggers.

Years 3 to 7, pilots. Deploy 100 to 1000 L pilots near shore, then 10 to 100 m³ offshore modules with full monitoring. Test multi barrier containment, validate economics, and begin benefit sharing once revenue starts.

Years 7 to 15, scale. Expand to hectare scale arrays only after demonstrating net positive ecological impact. Keep operations reversible. Integrate with supply chains and publish annual independent audits.

Practical next steps. Launch a 1-hectare floating pilot in a moderate coastal zone within three years, form a cross disciplinary consortium that includes Indigenous leaders and insurers, and publish open LCA data to speed regulatory acceptance. Adapt proven onshore bioprocess tools to harsh marine environments.

Risk and resilience checklist

- Positive ecological impact demonstrated at pilot scale, with public data.

- Multi barrier containment validated under storm and maintenance scenarios.

- Real time monitoring with automatic shutdown triggers in place and funded remediation.

- FPIC and benefit sharing agreements in force, with published engagement records.

- Insurance and restoration bonds sized to ecological risk, not only property loss.

Conclusion

Ocean biomanufacturing can shift our relationship with the sea from extraction to regeneration. The path is viable if we treat ecological protection as the hard requirement, use AI and autonomy to cut risk and cost, and close key gaps in containment, monitoring, standards, and finance. Start small, publish everything that matters for trust, and scale only when pilots show measurable ecosystem benefit. If we hold to that approach, we can deliver needed materials and services while leaving the ocean healthier than we found it.