Preamble

We recognize the profound intention behind efforts to address food insecurity and agricultural challenges in the Global South. Many seek to help, driven by genuine concern and a belief in technology’s potential.

Yet history compels us to pause.

Across Africa and beyond, well-intentioned technological interventions—imposed without deep understanding of local ecosystems, knowledge systems, or systemic realities—have too often led to unintended devastation. Fragile soils have been degraded, biodiversity eroded, water sources compromised, and farming communities displaced. The consequences are not merely short-term setbacks; they risk inflicting irreversible damage to ecological systems that sustain life and culture.

This analysis arises from an urgent truth: Africa’s ecosystems may not recover from another cycle of inappropriate technological imposition. The stakes transcend productivity metrics; they encompass the survival of indigenous knowledge, the sovereignty of communities, and the health of the planet itself.

We therefore call for a fundamental shift:

From prescriptive solutions to humble collaboration.

From external expertise to indigenous wisdom.

From technological haste to ecological reverence.

This is not a rejection of innovation, but a demand for integrity—a commitment to listen first, to assess holistically, and to empower locally. Only then can we break the cycle of harm and build truly resilient, sovereign food systems for generations to come.

Executive Summary

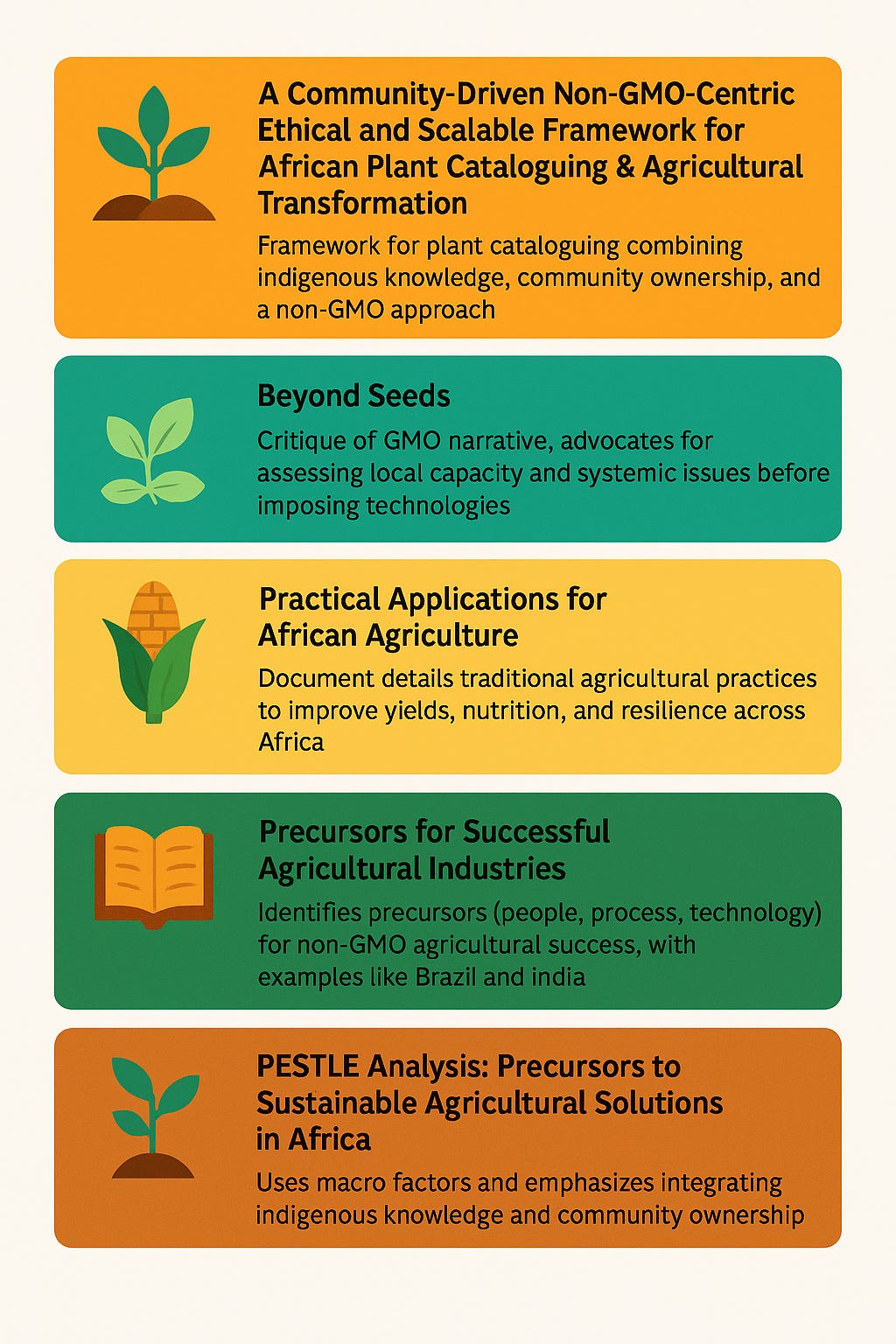

This analysis challenges the prevailing narrative that genetically modified organisms (GMOs) represent the optimal solution to food security challenges in developing nations. Through examination of agricultural development patterns in Africa and other Global South regions, we demonstrate that external technological impositions often overlook existing expertise, undermine local capacity, and perpetuate dependency rather than fostering genuine development. We propose the “ASSESS Before IMPOSE” framework as an alternative approach that prioritizes indigenous knowledge, addresses systemic challenges, and promotes agricultural sovereignty.

Introduction

The global discourse on food security has been dominated by technological determinism—the belief that advanced biotechnology, particularly GMOs, can solve hunger and agricultural challenges in developing nations. This narrative, while well-intentioned, fundamentally misdiagnoses the root causes of food insecurity and systematically undervalues indigenous agricultural knowledge systems that have sustained communities for millennia.

This framework emerges from evidence that countries in the Global South, particularly in Africa, possess substantial agricultural expertise, diverse crop varieties, and sophisticated farming systems adapted to local conditions. The persistence of food insecurity in these regions stems not from technological deficits but from governance failures, infrastructure gaps, and systemic issues that technological solutions alone cannot address.

Our analysis advocates for development approaches that prioritize local ownership, respect indigenous expertise, and tackle systemic challenges rather than imposing technological fixes that may create new dependencies while failing to resolve underlying problems.

My analysis artifacts

As usual performed outline analysis (the repository) : GMO

The Misdiagnosis Problem

External Perception Versus Local Reality

The conventional development narrative portrays African nations and other developing countries as lacking food production capacity and requiring external technological intervention. This perception fundamentally mischaracterizes the nature of food security challenges in these regions.

The Reality:

- Poor post-harvest storage infrastructure results in 30-40% food loss

- Governance failures and corruption divert resources from agricultural investment

- Inadequate transportation networks prevent efficient food distribution

- Political instability disrupts agricultural planning and implementation

- External exploitation perpetuates extractive economic relationships

The Expertise Paradox

Countries such as Nigeria, Ghana, Kenya, and Ethiopia possess:

- Extensive networks of trained agronomists and agricultural scientists

- Universities with robust agricultural research programs

- Traditional knowledge systems encompassing pest management, soil conservation, and climate adaptation

- Indigenous crop varieties adapted to local conditions and nutritional needs

- Established seed conservation practices and genetic resource management

The paradox lies in the systematic overlooking of this existing capacity in favor of external solutions that often prove incompatible with local conditions and farming systems.

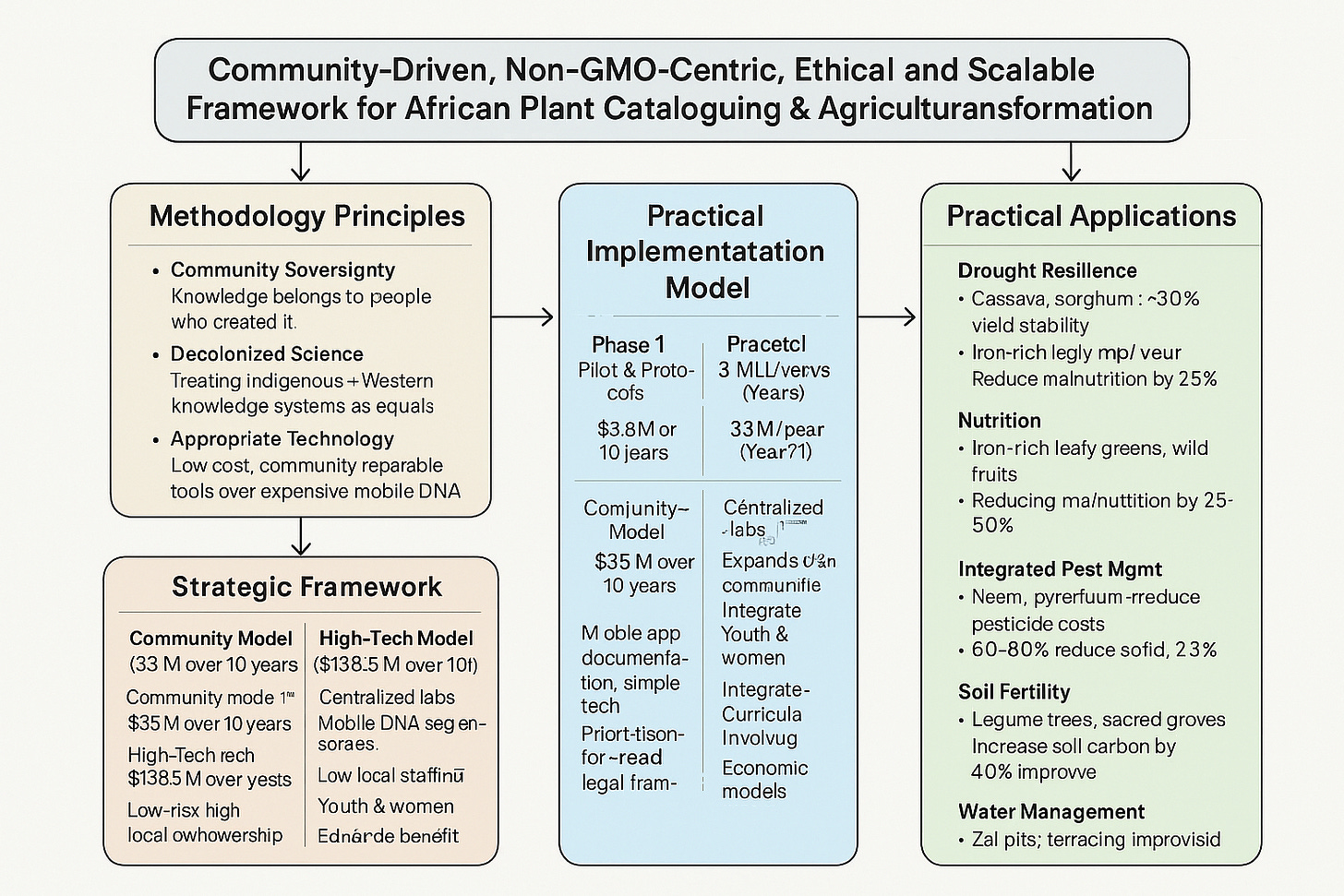

Phase 1: Comprehensive Local Assessment

Institutional Capacity Mapping

- Document existing agricultural research institutes and their capabilities

- Catalog Ministry of Agriculture resources, findings, and ongoing programs

- Assess university research capacity and faculty expertise

- Evaluate extension service networks and their reach

Indigenous Knowledge Inventory

- Traditional crop varieties and their specific properties

- Local nutritional requirements and dietary patterns

- Indigenous pest and disease management techniques

- Soil conservation and fertility management practices

- Climate adaptation strategies developed over generations

- Seed saving and genetic resource conservation methods

Infrastructure and Resource Analysis

- Current agricultural infrastructure and its utilization

- Research and development capabilities and gaps

- Market access and distribution networks

- Financial systems serving agricultural communities

Phase 2: Multi-Dimensional Impact Assessment

Economic Dimensions

- Comparative cost analysis: GMO seeds versus local alternatives

- Assessment of long-term economic dependencies created by external inputs

- Impact on local seed markets and farmer autonomy

- Analysis of debt implications for smallholder farmers

- Effects on agricultural trade balances and foreign exchange

Social and Cultural Considerations

- Impact on traditional farming communities and social structures

- Gender implications, particularly for women as primary food producers

- Cultural and spiritual significance of traditional crops

- Knowledge transfer patterns and intergenerational learning

- Community cohesion and social capital effects

Environmental Sustainability

- Biodiversity impact assessment, including effects on native varieties

- Ecosystem disruption potential and ecological interactions

- Long-term soil health implications

- Pesticide and herbicide usage requirements and environmental effects

- Climate resilience and adaptation capacity

Technological Appropriateness

- Compatibility with existing farming systems and practices

- Infrastructure requirements for successful implementation

- Technical support needs and local capacity for maintenance

- Sustainability of technological interventions without external support

Phase 3: Alternative Solution Development

Infrastructure-First Approach

- Investment in post-harvest storage and processing facilities

- Development of efficient transportation and distribution networks

- Market infrastructure improvements to connect farmers with consumers

- Financial infrastructure to support agricultural investment

Institutional Strengthening

- Enhanced funding for agricultural extension services

- Capacity building for research institutes and universities

- Policy implementation mechanism improvements

- Anti-corruption measures in agricultural sector governance

Indigenous Innovation Support

- Traditional crop improvement programs using conventional breeding

- Local seed development and conservation initiatives

- Farmer-to-farmer knowledge exchange networks

- Community-based agricultural conservation programs

Implementation Strategy

Immediate Actions (0-6 months)

- Methodology Development: Create standardized assessment tools and frameworks

- Partnership Formation: Establish relationships with African agricultural universities and research institutes

- Knowledge Base Creation: Begin documenting indigenous agricultural solutions and practices

- Advisory Board Formation: Recruit local agricultural experts and community leaders

Medium-term Objectives (6-18 months)

- Pilot Implementation: Complete comprehensive assessments in 3-5 target countries

- Research Publication: Document findings and develop alternative solution frameworks

- Stakeholder Engagement: Present findings to international development community

- Policy Advocacy: Develop and promote policy recommendations based on assessment results

Long-term Vision (18+ months)

- Institutional Development: Establish permanent research and advocacy organization

- Policy Influence: Work to reshape international development policies and practices

- Solution Scaling: Support expansion of successful indigenous agricultural innovations

- Sustainable Financing: Create enduring funding mechanisms for locally-led solutions

Business Model for Alternative Development

Agricultural Knowledge Exchange Platform

A digital platform connecting agricultural experts across developing countries, featuring:

- Database of indigenous solutions and research findings

- Direct access for policymakers to local expertise

- Peer-to-peer learning networks among practitioners

- Alternative to top-down solution imposition

Indigenous Agricultural Innovation Fund

Investment vehicle focusing on:

- Local agricultural research projects

- Scaling of proven indigenous solutions

- Infrastructure development using local knowledge

- Capacity building for local institutions

Pre-Intervention Assessment Services

Consulting services offering:

- Comprehensive agricultural ecosystem assessments

- Local expertise mapping and capacity evaluation

- Alternative solution identification and cost analysis

- Risk assessment for proposed interventions

Addressing Implementation Challenges

Industry Resistance

Strategy: Maintain evidence-based approach, partner with credible academic institutions, and emphasize complementary rather than competitive positioning.

Funding Constraints

Strategy: Demonstrate cost-effectiveness of assessment approach, develop revenue-generating services, and partner with organizations committed to sustainable development.

Political Sensitivities

Strategy: Maintain objective, research-based methodology, ensure local leadership and voice in all initiatives, and focus on sovereignty and self-determination themes.

Success Metrics and Evaluation

Quantitative Measures

- Number of comprehensive assessments completed

- Policy changes influenced at national and international levels

- Investment redirected from external impositions to local solutions

- Research partnerships established between institutions

- Documentation of indigenous knowledge systems

Qualitative Impact Indicators

- Recognition and validation of indigenous agricultural expertise

- Improved decision-making processes in agricultural development

- Enhanced capacity of local institutions and communities

- Preservation and strengthening of agricultural biodiversity

- Increased agricultural sovereignty and self-determination

Conclusion

The future of food security in the Global South depends not on the imposition of external technological solutions, but on the recognition, support, and development of existing local capacity and indigenous knowledge systems. The ASSESS Before IMPOSE framework provides a roadmap for more equitable and sustainable development practices that honor existing expertise while addressing genuine systemic challenges.

Countries across Africa and the broader Global South possess the agricultural knowledge, trained professionals, and indigenous solutions necessary to achieve food security. The primary obstacles are not technological but systemic: poor governance, inadequate infrastructure, and the perpetuation of extractive development relationships that prioritize external solutions over local capacity.

By implementing comprehensive assessments that map local expertise, understand cultural contexts, and address root causes, we can transcend the false choice between technological stagnation and external dependency. The alternative development model outlined here provides concrete pathways for supporting genuine agricultural advancement while preserving sovereignty and indigenous knowledge.

Success requires fundamental shifts in how we approach international development: from imposition to collaboration, from technological fixes to systemic solutions, and from external dependency to local empowerment. The stakes extend beyond agriculture to encompass questions of justice, sovereignty, and self-determination.

The choice before the international community is clear: continue perpetuating systems that extract wealth and knowledge from the Global South, or build genuine partnerships that recognize the dignity, expertise, and self-determination of all peoples. The path toward agricultural sovereignty begins with the simple but radical act of listening to and learning from those who have sustained their communities for generations.

Appendices

Appendix A: Crowdfunded Pre-Intervention Assessment Service

Service Portfolio:

- Comprehensive agricultural ecosystem assessments

- Local expertise mapping and capacity building analysis

- Alternative solution identification and economic modeling

- Risk assessment for proposed technological interventions

Target Client Base:

- International development organizations and multilateral institutions

- National government agencies responsible for agricultural policy

- Non-governmental organizations and private foundations

- Agricultural technology companies seeking responsible market entry

Revenue Model:

- Fee-for-service assessment contracts

- Subscription-based access to knowledge platform

- Training and capacity building services

- Policy consulting and advocacy support

Appendix B: Case Study Framework

Pilot Country Selection Criteria:

- Existing agricultural research capacity

- Documented indigenous knowledge systems

- Government openness to alternative approaches

- Presence of active civil society organizations

- Diverse agroecological zones and farming systems

Assessment Methodology:

- Participatory research approaches

- Community-based data collection

- Integration of scientific and traditional knowledge

- Multi-stakeholder validation processes

- Long-term monitoring and evaluation frameworks