Preamble

In Parts 1-5 of this series, we explored the commercialization of traditional foods, herbal remedies, and beverages as pathways to economic empowerment and cultural preservation. We examined the Global Superfood & Herbal Knowledge Platform, the strategic potential of ogogoro, traditional medicine systems, and the beverage sector’s transformation opportunities.

Now, we turn to perhaps the most urgent challenge facing African agriculture: building resilient food systems that can withstand climate shocks, support emergency response, and reverse environmental degradation. The continent’s experience with drought, desertification, and food insecurity has produced remarkable innovations—from plumpy’nut emergency nutrition to drought-resistant crops. Yet these solutions remain fragmented, under-documented, and underutilized across regions that share similar challenges.

This article examines how Africa can transform crisis response into sustainable development, creating circular agricultural economies that simultaneously address emergency needs, combat desertification, generate income, and restore ecological balance.

I find it challenging to write about building resilient food systems due to the complex ethical landscape and existing narratives surrounding the topic. The history of corruption, infrastructural challenges, and uneven development adds layers of difficulty. In the appendices I’ve created, I’ve outlined ethical and PESTLE considerations to help navigate these tensions more responsibly.

Series Navigation:

Building the Future of Food Part 1: A Global Superfood & Herbal Knowledge Platform Building the Future of Food Part 2: The Strategic Commercialisation of Ogogoro as a candidate Use Case

Building the Future of Food Part 3: Herbal Remedies and Traditional Medicine

Building the Future of Food Part 4: Hot Drinks, Coffee, Tea, Beverages and Desserts

Building the Future of Food Part 5: Energy Drinks

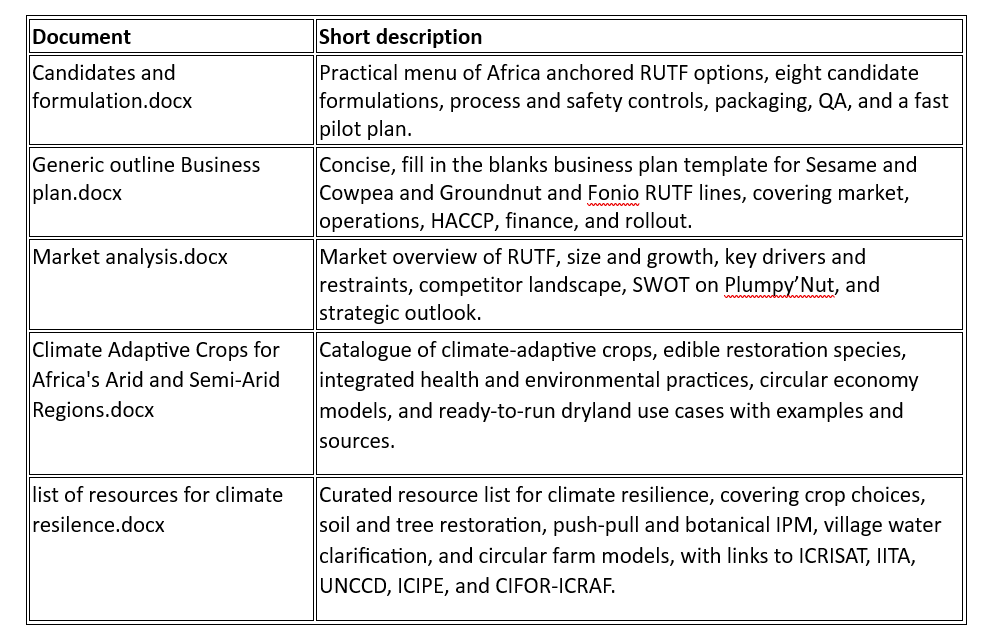

A usual some artefacts Research , Climate Adaptive Crops for Africa’s Arid and Semi-Arid Regions and formulations

The Emergency Food Security Landscape

The Plumpy’Nut Model: Lessons from a Success Story

Plumpy’nut, a peanut-based ready-to-use therapeutic food (RUTF), revolutionized emergency nutrition by providing:

- Locally sourceable ingredients (peanuts, oil, milk powder, sugar, vitamins)

- No water requirement for preparation (critical in contaminated water environments)

- Long shelf life without refrigeration

- High caloric density for treating severe acute malnutrition

- Economic benefits to local peanut farmers

Key Success Factors:

- Ground-level sourcing reducing transportation costs

- Cultural acceptability across diverse populations

- Scalable production with simple technology

- Integration of emergency relief with agricultural development

Beyond Peanuts: Expanding the Emergency Food Portfolio

Why Diversification Matters:

- Climate variability affects single-crop reliability

- Nutritional completeness requires variety

- Regional preferences enhance acceptance

- Multiple crops create economic resilience

- Reduced dependency on single supply chains

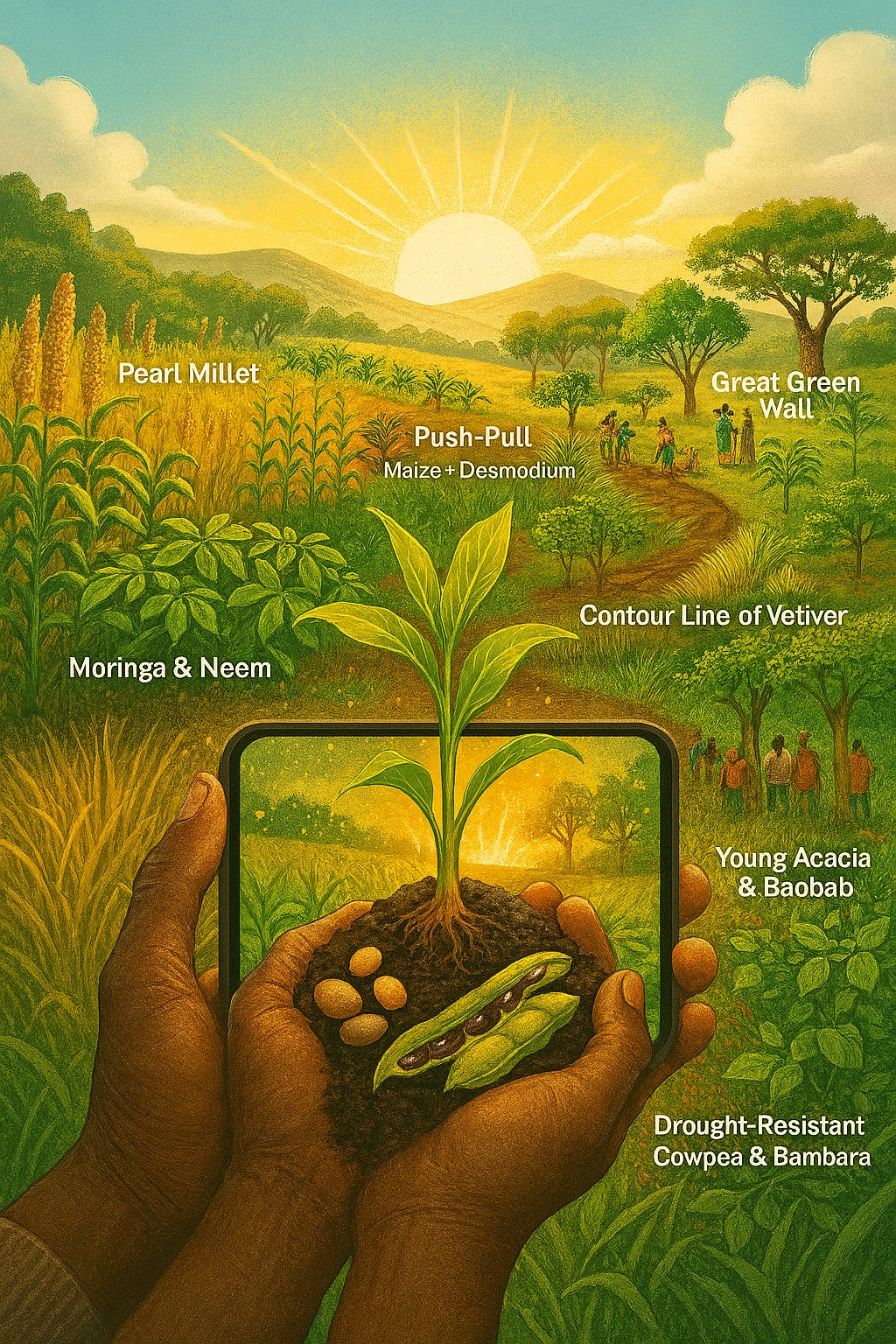

II. Climate-Adaptive Crops for Africa’s Arid and Semi-Arid Regions

Proven Drought-Resistant Candidates

1. Pearl Millet (Pennisetum glaucum)

- Climate Tolerance: Grows in 200-600mm annual rainfall

- Nutritional Profile: High in protein, iron, and calcium

- Emergency Potential: Can be processed into energy-dense foods

- Research Base: Extensively studied by ICRISAT (International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics)

- Regional Success: Sahel region, India, Namibia

- Soil Benefits: Deep roots prevent erosion, improves soil structure

2. Sorghum (Sorghum bicolor)

- Climate Tolerance: Highly drought-resistant, heat-tolerant

- Nutritional Profile: Gluten-free, high in antioxidants, protein

- Emergency Potential: Can be ground into fortified flour

- Hybrid Varieties: African Biofortified Sorghum (ABS) with enhanced nutrients

- Regional Success: Ethiopia, Sudan, Nigeria, Kenya

- Additional Uses: Animal feed, biofuel, building materials

3. Cowpea (Vigna unguiculata)

- Climate Tolerance: Thrives in hot, dry conditions

- Nutritional Profile: Excellent protein source, nitrogen-fixing legume

- Emergency Potential: Can be processed like chickpeas into protein pastes

- Research Base: IITA (International Institute of Tropical Agriculture)

- Regional Success: West Africa, East Africa

- Soil Benefits: Fixes atmospheric nitrogen, reducing fertilizer needs

4. Bambara Groundnut (Vigna subterranea)

- Climate Tolerance: Grows where other legumes fail

- Nutritional Profile: Complete protein, high lysine content

- Emergency Potential: Indigenous African crop with RUTF potential

- Research Gap: Underutilized despite enormous potential

- Regional Success: Traditional in sub-Saharan Africa

- Soil Benefits: Nitrogen fixation, drought-resistant ground cover

5. Moringa (Moringa oleifera)

- Climate Tolerance: Thrives in semi-arid tropics

- Nutritional Profile: Exceptionally high in vitamins A, C, calcium, protein

- Emergency Potential: Leaf powder as nutritional supplement

- Multi-purpose: Seeds for water purification, oil, livestock feed

- Regional Success: Pan-African adoption growing

- Soil Benefits: Fast-growing, minimal water needs, improves soil

6. Fonio (Digitaria exilis)

- Climate Tolerance: Grows in poor, sandy soils with minimal water

- Nutritional Profile: High in amino acids, particularly methionine and cystine

- Emergency Potential: Ancient grain with RUTF development potential

- Cultural Value: Sacred grain in some West African cultures

- Regional Success: Guinea, Mali, Burkina Faso, Nigeria

- Environmental Benefits: Matures quickly (6-8 weeks), prevents erosion

7. Cassava (Manihot esculenta) – Improved Varieties

- Climate Tolerance: Grows in marginal soils, drought-tolerant

- Nutritional Profile: Energy-dense carbohydrate source

- Hybrid Success: Biofortified varieties (yellow cassava) high in Vitamin A

- Emergency Potential: Long storage as dried flour

- Regional Success: Pan-African staple

- Considerations: Requires processing to remove cyanogenic compounds

III. Anti-Desertification and Soil Rehabilitation Strategies

The Great Green Wall Initiative: A Framework for Action

The African Union’s Great Green Wall project demonstrates integrated approaches:

- Scale: 8,000 km across 11 countries (Sahel region)

- Multi-purpose: Food security, climate adaptation, job creation

- Species diversity: Combination of trees, shrubs, and crops

- Community involvement: Local ownership and benefit-sharing

Key Anti-Desertification Plant Candidates

Trees and Shrubs for Stabilization

1. Acacia Species (Multiple varieties)

- Nitrogen-fixing properties

- Deep tap roots stabilize soil

- Provides fodder and fuelwood

- Multiple species adapted to different zones

2. Jatropha curcas

- Drought-resistant hedge/boundary plant

- Prevents soil erosion

- Seeds produce biofuel

- Caution: Not edible, toxic if ingested—use only for energy/boundaries

3. Baobab (Adansonia digitata)

- Iconic African tree with multiple uses

- Nutrient-rich leaves and fruit

- Deep roots prevent erosion

- Cultural and economic value

4. Prosopis species (Mesquite)

- Extremely drought-tolerant

- Nitrogen-fixing

- Pods provide animal feed

- Caution: Can become invasive—requires management

Ground Cover and Erosion Control

5. Vetiver Grass (Chrysopogon zizanioides)

- Deep root system (3+ meters) prevents erosion

- Does not spread aggressively

- Used in contour hedgerows

- Roots can be used for essential oils

6. Leucaena leucocephala

- Fast-growing, nitrogen-fixing

- Provides fodder and green manure

- Coppices well for continuous harvest

- Caution: Contains mimosine—requires proper livestock management

IV. Integrated Health and Environmental Solutions

Disease Vector Control Through Agricultural Design

Malaria Reduction Strategies

Plant-Based Interventions:

- Neem Tree (Azadirachta indica)

- Natural mosquito repellent

- Produces azadirachtin (organic insecticide)

- Medicinal properties for multiple ailments

- Improves soil fertility

- Lemongrass (Cymbopogon citratus)

- Contains citronella, natural mosquito repellent

- Can be grown as boundary crop

- Economic value as essential oil source

- Dual use: culinary and medicinal

- Eucalyptus species

- Mosquito-repelling properties

- Fast-growing biomass

- Considerations: High water consumption—use judiciously

- Can be used for essential oils and timber

Environmental Management:

- Proper drainage design to eliminate standing water

- Companion planting strategies

- Integrated Pest Management (IPM) approaches

Water Purification and Management

Moringa oleifera Seeds:

- Coagulant properties clarify turbid water

- Removes 90-99% of bacteria

- Simple, low-cost technology

- Seeds available from same trees providing nutrition

Sand Filtration Systems:

- Bio-sand filters using local materials

- Can be integrated with agricultural layouts

- Community-scale implementation

V. Circular Economy Models for Agricultural Resilience

Integrated Farm Systems Design

The Multi-Layer Approach

Layer 1: Canopy (Trees)

- Moringa, neem, baobab for multiple benefits

- Fruit trees (mango, papaya) for nutrition and income

- Timber species for long-term investment

Layer 2: Mid-Level (Shrubs/Tall Crops)

- Cassava, pigeon pea, sorghum

- Provides mid-story diversity

- Wind protection for lower crops

Layer 3: Ground Level (Annual Crops)

- Cowpeas, bambara groundnut, peanuts

- Pearl millet, fonio

- Rotating seasonal crops

Layer 4: Ground Cover

- Vetiver grass on contours

- Living mulches prevent erosion

- Nitrogen-fixing cover crops

Layer 5: Root Level

- Cassava, sweet potato

- Soil structure improvement

- Year-round food security

Animal Integration

Small Ruminants (Goats, Sheep):

- Browse on tree/shrub fodder

- Manure returns nutrients

- Controlled grazing prevents overgrazing

- Income diversification

Poultry:

- Pest control (insects, weeds)

- High-value protein source

- Manure for composting

- Quick return on investment

Aquaculture (where water available):

- Tilapia in small ponds

- Water for irrigation during dry season

- Fish waste fertilizes crops

- Nutritional diversity

Waste-to-Resource Loops

Composting Systems:

- Crop residues + animal manure

- Returns organic matter to soil

- Reduces chemical fertilizer dependency

- Produces biogas potential

Biogas Production:

- Animal waste → methane → cooking fuel

- Slurry byproduct → organic fertilizer

- Reduces deforestation for firewood

- Climate mitigation benefit

VI. Research Institutions and Knowledge Networks

Leading African Agricultural Research Centers

1. International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics (ICRISAT)

- Focus: Dryland cereals and legumes

- Locations: Mali, Niger, Zimbabwe, Kenya

- Expertise: Pearl millet, sorghum, chickpea, pigeonpea genetics

2. International Institute of Tropical Agriculture (IITA)

- Focus: Food security and agricultural development

- Headquarters: Nigeria; centers across Africa

- Expertise: Cassava, cowpea, maize, plantain improvement

3. World Agroforestry (ICRAF)

- Focus: Integrating trees into farming systems

- Research: Soil fertility, climate adaptation

- Regional programs across East and West Africa

4. African Agricultural Technology Foundation (AATF)

- Focus: Technology transfer and partnerships

- Work: Bringing improved varieties to smallholders

- Emphasis: Public-private partnerships

5. Forum for Agricultural Research in Africa (FARA)

- Coordinating body for African agricultural research

- Knowledge sharing across 49 countries

- Platform for best practice dissemination

6. National Agricultural Research Systems (NARS)

- Country-specific research institutes

- Examples: Kenya Agricultural and Livestock Research Organization (KALRO), Nigeria’s Institute for Agricultural Research (IAR)

- Local adaptation of technologies

Global Partnerships

- CGIAR (Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research): Network of 15 research centers

- FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization): Technical assistance and policy guidance

- Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa (AGRA): Seed systems and soil health programs

VII. Implementation Framework: Short, Medium, and Long-Term Strategies

Short-Term Actions (0-2 Years)

Emergency Preparedness:

- Diversify RUTF Production

- Pilot bambara groundnut-based emergency foods

- Develop fonio-enriched nutritional supplements

- Test cowpea-based protein pastes

- Document nutritional profiles and acceptability

- Seed Bank Establishment

- Community seed banks for climate-resilient varieties

- Preservation of traditional/indigenous varieties

- Distribution networks for emergency planting

- Training on seed saving and storage

- Knowledge Documentation

- Compile case studies of successful interventions

- Create farmer-to-farmer learning networks

- Develop mobile-accessible information platforms

- Translation into local languages

- Pilot Projects

- Select 5-10 communities per agroecological zone

- Implement integrated models

- Monitor and document outcomes

- Rapid iteration based on results

Medium-Term Strategies (2-5 Years)

Scaling Successful Models:

- Value Chain Development

- Processing facilities for drought-resistant crops

- Storage infrastructure to reduce post-harvest losses

- Market linkages for surplus production

- Quality standards and certification

- Policy Advocacy

- Integration into national agricultural policies

- Subsidies/incentives for climate-smart practices

- Land tenure security for long-term investments

- Cross-border cooperation for shared ecosystems

- Capacity Building

- Training programs for extension workers

- Farmer field schools on integrated practices

- Youth engagement in agricultural innovation

- Women’s leadership in food security initiatives

- Research Expansion

- Hybridization programs (non-GMO) for local adaptation

- Nutritional profiling of indigenous crops

- Climate modeling for crop suitability

- Economic analysis of circular systems

Long-Term Vision (5-15 Years)

Systemic Transformation:

- Regional Food Security Hubs

- Africa-to-Africa food assistance networks

- Reduced dependency on external aid

- South-South knowledge exchange

- Regional trade in climate-resilient crops

- Ecological Restoration

- Measurable reversal of desertification

- Increased biodiversity indicators

- Enhanced watershed function

- Carbon sequestration documentation

- Economic Resilience

- Diversified income sources for smallholders

- Climate-risk insurance products

- Value-added processing enterprises

- Export markets for indigenous superfoods

- Knowledge Leadership

- African centers of excellence in dryland agriculture

- Global best practice dissemination

- Academic programs in climate-smart agriculture

- Innovation hubs for agricultural technology

VIII. Ecological Considerations and Sustainability Metrics

Environmental Impact Assessment

Positive Indicators:

- Increased soil organic matter

- Enhanced water retention capacity

- Biodiversity improvements (pollinators, soil microbes, bird species)

- Reduced erosion rates

- Carbon sequestration in soils and biomass

Risk Mitigation:

- Invasive Species: Careful selection and management protocols

- Monoculture Avoidance: Diversity as core principle

- Water Balance: Matching crops to rainfall patterns

- Nutrient Cycling: Closed-loop systems minimize external inputs

Monitoring and Evaluation Framework

Key Performance Indicators:

- Food Security Metrics

- Household dietary diversity scores

- Months of adequate food provisioning

- Child malnutrition rates

- Emergency response capacity

- Environmental Health

- Soil organic carbon levels

- Vegetative cover percentage

- Water table depth/stability

- Species diversity indices

- Economic Outcomes

- Household income diversification

- Reduction in food purchase expenditure

- Value of surplus production sold

- Return on investment timelines

- Social Indicators

- Women’s participation and decision-making

- Youth retention in agriculture

- Community cohesion metrics

- Knowledge transfer rates

IX. Case Studies: Successes and Lessons Learned

Case Study 1: Niger’s Farmer-Managed Natural Regeneration (FMNR)

Context: Severe deforestation and soil degradation in the Sahel

Intervention:

- Farmers protected and managed tree regrowth on farmland

- Integration of trees with crops (agroforestry)

- Community-led, minimal external inputs

Results:

- 5 million hectares of land restored (1980s-2000s)

- 200 million new trees

- Increased crop yields (100+ kg/hectare grain increase)

- Improved food security for 2.5 million people

Lessons:

- Local knowledge and ownership crucial

- Low-cost, high-impact interventions possible

- Policy support enables scaling

- Long-term commitment yields compounding benefits

Case Study 2: Kenya’s Push-Pull Technology for Maize and Sorghum

Context: Stem borer pests and Striga weed devastation

Intervention:

- Intercropping maize/sorghum with desmodium (repels pests, suppresses Striga)

- Border planting of Napier grass (attracts and traps pests)

- Developed by ICIPE (International Centre of Insect Physiology and Ecology)

Results:

- 70-80% reduction in stem borer damage

- Striga weed suppression

- Increased milk production (desmodium as livestock fodder)

- Improved soil fertility (nitrogen fixation)

- Adopted by 130,000+ farmers across East Africa

Lessons:

- Integrated approaches address multiple problems

- Ecological principles can replace chemical inputs

- Tangible economic benefits drive adoption

- Scientific research + traditional farming practices = innovation

Case Study 3: Ethiopia’s Community-Based Watershed Management

Context: Highland degradation, soil erosion, water scarcity

Intervention:

- Terracing on hillsides

- Tree planting on steep slopes

- Check dams for water harvesting

- Community bylaws for sustainable use

Results:

- Groundwater recharge increased

- Spring flow restoration

- Crop productivity improvements

- Reduced vulnerability to drought

Lessons:

- Watershed-scale planning essential

- Community institutions must govern resources

- Government support + local action = success

- Multi-year perspective necessary

Case Study 4: Malawi’s Agroforestry Food Security Programme

Context: Soil fertility depletion, food insecurity

Intervention:

- Planting Faidherbia albida (nitrogen-fixing tree) in fields

- Intercropping with maize

- Tree pruning for green manure

Results:

- Maize yields doubled (from 1 ton/ha to 2-3 tons/ha)

- No chemical fertilizer needed in mature systems

- Improved food security

- Carbon sequestration co-benefit

Lessons:

- Patience required (3-5 years for full benefits)

- Species selection critical for compatibility

- Training and demonstration farms accelerate adoption

- Food security and climate mitigation aligned

X. Logistics and Transportation Considerations

Intra-African Distribution Networks

Current Challenges:

- Poor road infrastructure in rural areas

- Cross-border trade barriers

- Limited cold chain capacity

- High transportation costs

Solutions:

- Decentralized Production

- Regional processing centers reduce transport needs

- Local production for local consumption

- Strategic reserves in multiple locations

- Appropriate Packaging

- Shelf-stable formulations (like plumpy’nut)

- Lightweight, durable packaging

- Bulk transport with local repackaging

- Digital Coordination

- Mobile platforms for supply-demand matching

- Logistics optimization software

- Real-time inventory tracking

- Infrastructure Investment

- Rural road improvement programs

- Solar-powered cold storage

- Rail and river transport where viable

Emergency Logistics Protocols

Pre-Positioning:

- Strategic reserves in drought-prone regions

- Community-level buffer stocks

- Early warning systems trigger preemptive distribution

Rapid Response:

- Pre-established distribution partnerships

- Local procurement prioritized

- Cash transfers + local markets where functional

XI. Financing and Investment Models

Funding Sources

Public Sector:

- National agricultural budgets

- Climate adaptation funds (Green Climate Fund, Adaptation Fund)

- Regional development banks (AfDB, IFAD)

- Bilateral development assistance

Private Sector:

- Impact investors seeking social + environmental returns

- Agricultural value chain companies

- Carbon credit mechanisms

- Microfinance institutions for farmer loans

Innovative Mechanisms:

- Weather-indexed insurance

- Results-based financing

- Blended finance models

- Diaspora investment platforms

Return on Investment

Economic Returns:

- Increased agricultural productivity

- Reduced input costs (fertilizers, pesticides)

- New income streams (carbon credits, biodiversity payments)

- Decreased emergency response costs

Social Returns:

- Improved health and nutrition

- Enhanced food security

- Job creation in rural areas

- Youth engagement in agriculture

Environmental Returns:

- Ecosystem services valuation

- Climate change mitigation

- Biodiversity conservation

- Water security

XII. Overlooked Considerations and Cross-Cutting Issues

Gender Dynamics

Women as Key Actors:

- 60-80% of food production in Africa done by women

- Control of resources often limited despite labor contribution

- Nutritional knowledge concentrated among women

Gender-Responsive Design:

- Land ownership and tenure security for women

- Access to credit and inputs

- Labor-saving technologies

- Women’s leadership in decision-making

Indigenous Knowledge Integration

Value of Traditional Practices:

- Centuries of experimentation and adaptation

- Context-specific ecological wisdom

- Cultural appropriateness ensures adoption

Respectful Engagement:

- Co-creation, not top-down imposition

- Documentation with community consent

- Benefit-sharing from commercialization

- Preservation of intellectual property rights

Youth Engagement

Making Agriculture Attractive:

- Technology integration (mobile apps, drones, precision agriculture)

- Value-added processing opportunities

- Market linkages to urban consumers

- Entrepreneurship training and support

Conflict and Fragile Contexts

Special Considerations:

- Food security as peacebuilding tool

- Resilience to displacement

- Cross-border pastoral migration

- Resource competition mediation

Climate Justice

Equitable Approaches:

- Africa contributes least to climate change but suffers most

- Technology transfer without onerous IP restrictions

- Climate finance as compensation, not charity

- African leadership in solution design

Conclusion: From Crisis to Opportunity

Africa’s agricultural challenges—climate variability, desertification, food insecurity, environmental degradation—are undeniably severe. Yet they also present an unprecedented opportunity for transformation. The continent possesses:

- Biodiversity: Thousands of indigenous crop species adapted to harsh conditions

- Innovation capacity: Farmer-led experimentation and adaptation

- Young population: Energy and creativity for new approaches

- Land availability: Space for ecological restoration at scale

- Growing markets: Both domestic demand and global interest in African products

The path forward requires moving beyond the emergency mindset that has dominated food security discourse. While crisis response remains essential, the real breakthrough lies in building systems that prevent crises while regenerating ecosystems, supporting livelihoods, and nourishing communities.

The vision is clear: African farmers at the center of climate-resilient food systems that draw on indigenous knowledge, cutting-edge research, and ecological principles to create abundance where scarcity once reigned.

The tools exist: From bambara groundnuts to vetiver grass, from farmer-managed natural regeneration to push-pull technology, solutions have been proven in African contexts.

The moment is now: Climate change accelerates, populations grow, and conventional approaches falter. Africa can lead the world in demonstrating that food security, environmental restoration, and economic development are not competing priorities but interconnected solutions.

This is not about waiting for external rescue. It is about African communities, researchers, policymakers, and entrepreneurs building the future they want to inhabit—a future where disaster relief gives way to resilient abundance, where deserts bloom with purpose, and where food security becomes the foundation for broader prosperity.

Action Plan: Next Steps for Stakeholders

For Policymakers

- Immediate (0-6 months):

- Conduct national inventory of climate-resilient crop varieties

- Review agricultural subsidies to incentivize diversity

- Establish inter-ministerial task force (Agriculture, Environment, Health, Trade)

- Short-term (6-24 months):

- Pilot integrated farm systems in 3-5 agroecological zones

- Develop national agroforestry and soil restoration strategy

- Create enabling legislation for seed banks and variety preservation

- Medium-term (2-5 years):

- Integration into National Adaptation Plans (NAPs)

- Regional cooperation agreements for food security

- Investment in agricultural research infrastructure

For Research Institutions

- Immediate:

- Literature review of existing studies on candidate crops

- Establish research priorities based on gaps

- Create database of African agricultural innovations

- Short-term:

- Participatory trials with farmer communities

- Nutritional profiling of indigenous crops

- Economic modeling of integrated systems

- Medium-term:

- Hybridization programs for local adaptation (non-GMO)

- Climate suitability modeling

- Publication and dissemination of findings

For NGOs and Development Partners

- Immediate:

- Partner with existing farmer organizations

- Document and share success stories

- Establish farmer-to-farmer learning networks

- Short-term:

- Pilot integrated approaches in target communities

- Capacity building for extension workers

- Support seed bank establishment

- Medium-term:

- Scale proven models across regions

- Develop market linkages for farmers

- Advocate for policy change based on evidence

For Private Sector

- Immediate:

- Assess opportunities in climate-resilient value chains

- Engage with research institutions for innovation partnerships

- Explore impact investment options

- Short-term:

- Develop processing facilities for indigenous crops

- Create market demand through product development

- Invest in smallholder capacity

- Medium-term:

- Build regional supply chains

- Scale successful business models

- Explore export markets for African superfoods

For Farmers and Communities

- Immediate:

- Start seed saving of traditional varieties

- Experiment with one or two new climate-resilient crops

- Organize farmer learning groups

- Short-term:

- Implement integrated practices on portion of land

- Document what works in local conditions

- Share knowledge with neighbors

- Medium-term:

- Diversify income through value-added processing

- Participate in farmer organizations and cooperatives

- Mentor other farmers in successful practices

For Individual Supporters

- Immediate:

- Educate yourself on African agricultural innovations

- Support organizations working in this space

- Advocate for policy changes in your country

- Short-term:

- Purchase African products that support sustainable agriculture

- Amplify African voices in climate and food security discussions

- Consider volunteering skills or expertise

- Medium-term:

- Invest in African agricultural enterprises

- Support capacity building programs

- Foster partnerships between institutions in Global North and South

Final Reflection

Building the future of food in Africa is not about imposing external solutions but about recognizing, supporting, and scaling the innovations already emerging from the continent. It requires humility to learn from traditional knowledge, courage to try new integrated approaches, and patience to nurture long-term transformation.

The crops are ready. The knowledge exists. The people are willing. What remains is to connect these elements into coherent systems, supported by appropriate policies, adequate financing, and genuine partnerships.

In the face of global climate uncertainty, Africa is not a problem waiting for solutions—it is a laboratory of resilience, a birthplace of innovation, and potentially a beacon showing the world how to grow food in harmony with nature rather than despite it.

The question is not whether Africa can feed itself sustainably. The question is whether the rest of the world will learn from Africa quickly enough to ensure everyone can eat in the decades ahead.

Appendices: Ethical considerations