Preamble

The missing critical layer in nature-inspired innovation

Biomimicry is often presented as an antidote to extractive, brittle design. By learning from organisms and ecosystems refined over billions of years, we are promised solutions that are efficient, resilient, and life-conducive. And sometimes that promise holds.

But just as often, biomimicry-inspired projects quietly underperform, stall, or are abandoned not because nature “failed,” but because our translation of nature did.

This article explores the failure modes and anti-patterns that repeatedly appear in applied biomimicry. It is not a rejection of the discipline, but a necessary maturation step: moving from inspiration to accountability.

The reflections here build directly on the fictional use cases and framework explorations in the attached Sleep, Eat, Wear : https://ideaswiz.com/biomimicry-sleep-eat-wear-design allegory and The Convergence framework:https://ideaswiz.com/biomimicry-design-framework-the-convergence , by examining where such approaches can—and do—break down in practice .

1. Common Misinterpretations of Biological Analogies

One of the most persistent anti-patterns in biomimicry is analogy literalism: assuming that because something looks like nature, it works like nature.

The trap

Designers often copy:

- Shapes (lotus leaves, shark skin, honeycombs)

- Textures (riblets, scales, microstructures)

- Geometries (spirals, branching forms)

…without fully understanding:

- The conditions under which the biological strategy works

- The tradeoffs it accepts

- The system context that makes the function viable

For example, lotus-inspired self-cleaning surfaces frequently ignore the ecological reality that lotus leaves are:

- Replaced frequently

- Grown at ambient temperatures

- Embedded in wet, self-renewing ecosystems

When translated into durable architectural coatings or consumer materials, the same microstructures may require toxic chemistries, energy-intensive manufacturing, or frequent maintenance—negating the original ecological advantage .

Anti-pattern name

“Form Equals Function” Fallacy

Signal to watch for

If the design explanation stops at “it looks like X in nature”, failure is likely.

2. When Form-Level Mimicry Creates Fragile Systems

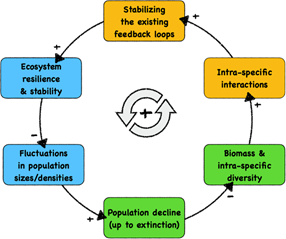

Nature rarely optimizes single variables in isolation. Most biological strategies are:

- Redundant

- Adaptive

- Embedded in networks of feedback

Engineered systems inspired only at the form level often lack these properties.

The problem with isolated features

Many biomimetic projects succeed in controlled environments but fail when scaled or integrated:

- Buildings with biomimetic ventilation overridden by occupant behavior

- Antimicrobial surfaces that disrupt broader indoor ecological balance

- Structural forms optimized for static loads but brittle under dynamic use

A recurring pattern is brittleness at scale. Biological systems operate at specific size ranges, material constraints, and energy flows. When designers upscale without re-deriving the governing principles, performance collapses.

Even celebrated projects, such as termite-inspired passive cooling systems, show performance degradation when:

- Users intervene

- Maintenance regimes differ

- Climatic assumptions shift .

Anti-pattern name

“Single-Feature Biomimicry”

Signal to watch for

If removing one component causes total system failure, the design is not behaving like nature it is behaving like a machine.

3. Cultural Rejection Despite Technical Elegance

Technical success does not guarantee social acceptance. Biomimicry projects frequently underestimate cultural, ethical, and symbolic dimensions.

Where rejection emerges

Common failure points include:

- Perceived greenwashing: Nature-inspired aesthetics masking extractive supply chains

- Biopiracy concerns: Commercialization of indigenous ecological knowledge without consent or reciprocity

- Value misalignment: Technologies that conflict with local norms despite efficiency gains

Research shows that users do not automatically trust or prefer biomimetic solutions. In several studies, nature-inspired buildings were rated no more sustainable or desirable than conventional ones when users perceived them as superficial or inauthentic .

More critically, when biomimicry is applied to domains like surveillance, control, or behavioral manipulation, it can trigger ethical backlash even if technically impressive.

Anti-pattern name

“Nature as Justification”

Signal to watch for

If “it’s inspired by nature” is used to silence critique rather than invite dialogue, rejection is likely.

4. Metrics That Looked Good on Paper but Failed in Use

Another silent killer of biomimicry projects is metric myopia.

The lab-to-life gap

Common metrics emphasize:

- Energy efficiency under ideal conditions

- Material performance in isolation

- Short-term cost or performance gains

What is often missed:

- Lifecycle toxicity

- Maintenance energy

- Supply chain fragility

- Behavior-driven performance erosion

For example, mussel-inspired adhesives perform exceptionally in laboratory settings but require complex chemistries and controlled conditions that are difficult to industrialize affordably or safely. The result is high R&D cost, low adoption, and stalled commercialization .

Similarly, designs that score well against abstract “Life’s Principles” may still fail if:

- They cannot be repaired locally

- They depend on rare materials

- They degrade unpredictably over time

Anti-pattern name

“Metric Substitution”

Signal to watch for

If success is defined only by surrogate metrics rather than lived performance, long-term failure risk is high.

5. From Nature-Washing to Design Maturity

These failure modes do not argue against biomimicry. They argue against immature biomimicry.

A more robust practice requires:

- Prioritizing process- and system-level mimicry over form

- Stress-testing designs socially, not just technically

- Treating Life’s Principles as constraints, not marketing language

- Designing for misuse, maintenance, and adaptation—not ideal behavior

The Sleep, Eat, Wear allegory highlights how dignity, locality, and low-energy solutions can emerge from biological insight. This article adds the necessary counterweight: understanding how easily those insights can be misapplied without rigor .

Closing Thought: Nature Is a Teacher, Not a Template

Nature does not hand us blueprints. It offers strategies, shaped by context, compromise, and time.

Biomimicry fails when we extract patterns without responsibility and succeeds when we translate principles with humility.

Design maturity begins not with copying what nature looks like, but with understanding how nature survives failure.

Appendices

Below is a practical, reusable diagnostic tool followed by annotated case studies you can reference when evaluating or teaching biomimicry projects. This is designed to sit alongside your existing Biomimicry Design Framework as the critical failure filter the part most frameworks omit.

Nature Is Not a Blueprint

A Diagnostic Checklist & Casebook for Biomimicry Design

PART I — BIOMIMICRY FAILURE MODES DIAGNOSTIC

A pre-flight checklist for biomimicry projects

Use this as:

- a gate review before prototyping,

- a design critique tool, or

- a post-mortem framework when projects underperform.

Score each section Low / Medium / High Risk.

Any High Risk should trigger redesign or deeper investigation.

1. Biological Analogy Integrity Check

(Avoiding superficial mimicry)

Ask:

- ☐ Have we identified the function, not just the form?

- ☐ Do we understand why this strategy evolved in nature?

- ☐ Are we clear on the environmental conditions (temperature, scale, renewal rate) that make it work?

- ☐ What biological tradeoffs does this strategy accept?

Red Flags

- “It looks like…” is the primary justification

- No discussion of constraints or failure modes in nature

Anti-pattern triggered: Form = Function Fallacy

2. Level-of-Mimicry Test

(Form vs. process vs. system)

Classify your design honestly:

- ☐ Form-level (shape, texture, geometry)

- ☐ Process-level (flows, feedback, self-regulation)

- ☐ System-level (networks, redundancy, cycles)

Ask:

- ☐ If one component fails, does the system degrade gracefully?

- ☐ Are there feedback loops, or is performance static?

Red Flags

- Single-feature “biomimetic add-ons”

- No redundancy or adaptability

Anti-pattern triggered: Single-Feature Biomimicry

3. Scale & Translation Stress Test

(Where most projects quietly fail)

Ask:

- ☐ Has performance been tested beyond lab or prototype scale?

- ☐ Does scaling change physics, energy flows, or material behavior?

- ☐ What happens when users behave “incorrectly”?

Red Flags

- Large performance drop (>20%) outside controlled conditions

- Reliance on perfect use or maintenance

Anti-pattern triggered: Brittle-at-Scale Design

4. Cultural & Ethical Fit Check

(Technical success ≠ social acceptance)

Ask:

- ☐ Does this align with local cultural values and aesthetics?

- ☐ Could this be perceived as greenwashing or extractive?

- ☐ Are there ethical tensions (surveillance, control, biopiracy)?

Red Flags

- “Nature-inspired” used to deflect criticism

- Indigenous or ecological knowledge used without reciprocity

Anti-pattern triggered: Nature as Justification

5. Metric Reality Check

(Paper success vs lived performance)

Ask:

- ☐ Do metrics include full lifecycle impacts (materials, toxicity, end-of-life)?

- ☐ Have we tested maintenance, misuse, and degradation?

- ☐ Are costs and complexity rising faster than benefits?

Red Flags

- Metrics stop at efficiency or aesthetics

- Sustainability claims ignore production realities

Anti-pattern triggered: Metric Substitution

🚦 Interpretation Guide

- 0–1 High Risk flags: Proceed with confidence

- 2–3 High Risk flags: Redesign required

- 4+ High Risk flags: Conceptual rethink recommended

PART II — ANNOTATED CASE STUDIES

Where biomimicry succeeded, strained, or failed

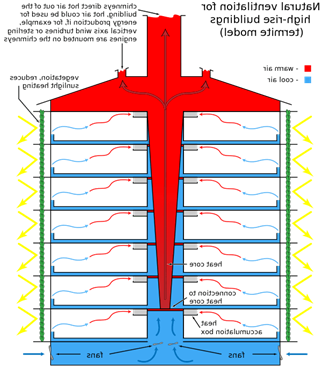

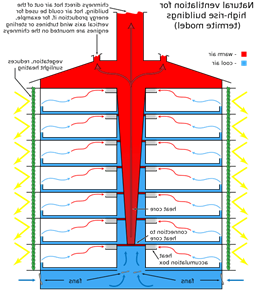

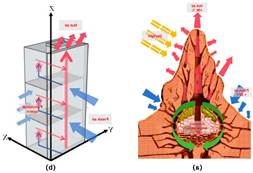

A. Architecture Case Study

Eastgate Centre

Biological inspiration: Termite mound thermoregulation

Level of mimicry: Process-level (airflow, thermal mass)

What worked

- Reduced mechanical cooling demand

- Climate-appropriate design logic

Where it strained

- Occupants overrode passive systems

- Performance declined without behavioral alignment

- Replication in other climates underperformed

Diagnostic flags triggered

- ⚠ Scale & behavior mismatch

- ⚠ Assumed passive systems would remain untouched

Lesson

Biomimicry must account for human behavior as an ecological force.

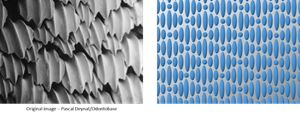

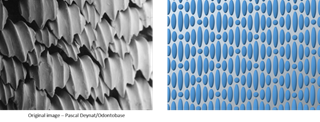

B. Materials Case Study

Shark-Skin–Inspired Antibacterial Surfaces

Biological inspiration: Dermal denticles reducing biofouling

Level of mimicry: Form-level (microtexture)

What worked

- Reduced bacterial adhesion in lab conditions

- Non-chemical antimicrobial strategy

Where it failed

- Manufacturing required toxic or energy-intensive processes

- Effectiveness dropped with wear, dirt, and cleaning

- Maintenance negated sustainability gains

Diagnostic flags triggered

- ⚠ Form-level mimicry only

- ⚠ Lifecycle metric failure

Lesson

Nature’s performance depends on context + renewal, not static surfaces.

C. Systems Case Study

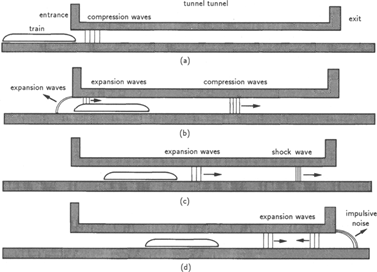

Shinkansen Bullet Train (Kingfisher Nose)

Biological inspiration: Kingfisher beak reducing pressure shock

Level of mimicry: Form + physics translation

What worked

- Reduced tunnel sonic boom

- Improved energy efficiency and noise reduction

Hidden tradeoff

- Required high-energy materials and precision manufacturing

- Sustainability gains were operational, not systemic

Diagnostic flags triggered

- ⚠ Metric substitution (operational vs lifecycle sustainability)

Lesson

Solving one problem biomimetically does not guarantee holistic sustainability.

SYNTHESIS: THE MASTER ANTI-PATTERN

Across architecture, materials, and systems, the same root failure appears:

Extracting a pattern without inheriting its constraints.

Nature works because it:

- Accepts limits

- Uses redundancy

- Adapts continuously

- Optimizes across systems, not features

HOW TO USE THIS GOING FORWARD

You can now:

- Insert the Diagnostic Checklist as a mandatory step in The Convergence framework

- Use the case studies as teaching counterexamples

- Turn this into a design review rubric for studios, NGOs, or innovation teams

Image references and links

Below are clean, reusable image reference sets you can directly associate with the diagnostic tool and annotated case studies. These are framed as visual evidence references, not decoration, so they can be cited in articles, slide decks, or teaching materials.

Architecture — Passive Cooling & Behavioral Breakdown

Eastgate Centre

Use these images to illustrate:

- Translation from termite mound airflow to building-scale ventilation

- The difference between biological system behavior and human-inhabited systems

- How passive systems depend on occupant behavior and maintenance

Best paired diagnostic sections:

✔ Scale & Translation Stress Test

✔ Cultural & Behavioral Fit Check

AskNature — “Passively Cooled Building Inspired by Termite Mounds” (Eastgate Centre)

https://asknature.org/innovation/passively-cooled-building-inspired-by-termite-mounds

Arup project page — “Eastgate” (design + natural ventilation explanation)

https://www.arup.com/projects/eastgate

ConstructSteel — Eastgate Centre overview (includes performance claims and design description)

Materials — Microtexture Without Ecosystem Context

Shark-Skin–Inspired Antibacterial Surfaces

Use these images to illustrate:

- Denticle microstructure at laboratory scale

- Application on synthetic materials

- Wear, fouling, and loss of function over time

Best paired diagnostic sections:

✔ Level-of-Mimicry Test

✔ Metric Reality Check

Peer-reviewed (PubMed Central) — “Surface micropattern limits bacterial contamination” (Sharklet micropattern)

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4166016

AskNature — “Antibacterial Film Inspired by Sharks” (Sharklet overview)

https://asknature.org/innovation/antibacterial-film-inspired-by-sharks

Peer-reviewed (PubMed Central) — “Bioinspired Photocatalytic Shark-Skin Surfaces…” (durable multifunctional surfaces)

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6013830

Transportation Systems — Successful Physics, Partial Sustainability

Shinkansen Bullet Train

Use these images to illustrate:

- Clear biological analogy (beak → pressure wave reduction)

- Effective form–physics translation

- Hidden tradeoffs in materials, energy, and lifecycle impact

Best paired diagnostic sections:

✔ Biological Analogy Integrity Check

✔ Metric Substitution Anti-Pattern

AskNature — “High Speed Train Inspired by the Kingfisher”

https://asknature.org/innovation/high-speed-train-inspired-by-the-kingfisher

Trellis (GreenBiz) — “How one engineer’s birdwatching made Japan’s bullet train better” (background + engineering narrative)

https://trellis.net/article/how-one-engineers-birdwatching-made-japans-bullet-train-better

Cross-Cutting Diagnostic Visuals

Form vs Process vs System-Level Mimicry

Use these images to:

- Teach hierarchy of mimicry maturity

- Show why isolated features fail

- Contrast mechanical optimization with ecological resilience

Best paired diagnostic sections:

✔ Level-of-Mimicry Test

✔ Single-Feature Biomimicry Anti-Pattern

Peer-reviewed (PubMed Central) — “Promises and Presuppositions of Biomimicry” (explicitly discusses levels: form/process/ecosystem)

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7557929

Biomimicry Institute — “What is biomimicry” (official definitions + framing) https://biomimicry.org/

EOMEGA — “A Biomimicry Primer” (mentions form, process, system levels in plain language)

https://www.eomega.org/article/a-biomimicry-primer

How to Use These Image References Effectively

Recommended practice (important):

- Always caption images with what failed or degraded, not just what inspired

- Pair every image with a diagnostic question, not a claim

- Avoid using images as proof of sustainability use them as evidence for scrutiny

Example caption format:

“Shark-skin-inspired microtextures demonstrate strong bacterial resistance in controlled conditions but degrade rapidly under abrasion and cleaning—triggering a Metric Reality Check failure.”