Preamble

A Thought Experiment in AI Accessibility and E-Waste Reduction: What This Document Is (And Isn’t)

This Software Requirements Specification is not a formalized methodology or a prescriptive solution. Think of it as throwing paint at a wall to see what sticks—an exploration of possibilities rather than a definitive roadmap.

The core question driving this work is simple: In a world where AI capabilities are increasingly essential, but access to AI-capable hardware remains unequal, what alternatives exist?

This document examines one possibility: repurposing aging laptops into distributed AI infrastructure. It’s a snapshot—a conceptual framework that orchestrates various ideas people have had about running AI on discrete, lower-powered devices.

My Personal Perspective

If you can afford proper AI-compliant hardware, get it. This approach should be considered as a supplement, not a replacement, for dedicated AI infrastructure. The question isn’t whether this is the optimal solution—it clearly isn’t. The questions are:

- Is it worth investigating? I believe yes.

- Is it worth doing? That depends on your context, constraints, and priorities.

The Reality Check

We often hear that AI computing will be accessible to everyone—that people worldwide will run their own personal AI models. The reality is quite different.

In the Global South and underserved communities globally, access to cutting-edge AI hardware is not just expensive—it’s often impossible. Yet the need for AI capabilities in these contexts is real and growing:

- Education: Students and researchers need hands-on access to AI tools

- Accessibility: AI-powered assistive technologies can transform lives

- Circularity: Extending hardware lifecycles reduces electronic waste

- Sustainability: Local computing can reduce dependency on distant cloud infrastructure

How these priorities are balanced—education versus accessibility versus environmental impact—is something each community and organization must consider for themselves.

Who This Is For

This document may resonate with different audiences for different reasons:

The Open Source Developer: You might see this as a framework for creating orchestration software for repurposed laptop clusters—perhaps as an open-source project that democratizes AI infrastructure.

The Resource-Constrained Organization: You might be thinking, “I can’t afford dedicated AI hardware. What can I do with what I already have for my specific use case?”

The Sustainability Advocate: You might view this through the lens of e-waste reduction and circular economy principles.

The Educator: You might see an opportunity to provide hands-on AI learning experiences with accessible hardware.

Consider This a Raw Idea

This is a very raw concept that requires—if you choose to pursue it—significantly more investigation and analysis. I’m certain that someone, somewhere, will pick up these ideas and run with them in directions I haven’t imagined.

The goal isn’t to provide all the answers. It’s to inspire action, to show what might be possible, and to distill a methodology and software requirements that could form the foundation for something more developed.

What You’ll Find Here

After reading through this document and its attendant parts, ask yourself:

- What methodology can be distilled from this exploration?

- What software requirements emerge as truly essential?

- Is this approach worth pursuing for your specific context?

- What would you need to change or add to make this viable for your use case?

A Final Note

Not everyone expects AI to be accessible to the entire world. Many people understand that significant barriers exist. But perhaps, with creativity, collaboration, and a willingness to work with what we have, we can make meaningful progress toward that vision even if imperfectly, even if incrementally.

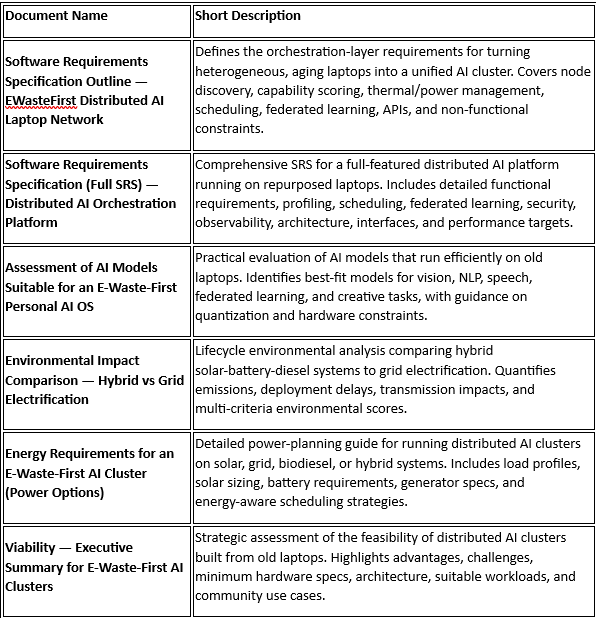

As usual some artifacts Network laptops for AI access

Executive Summary

The artificial intelligence revolution has predominantly been the domain of hyperscale cloud providers and organizations with access to expensive GPU farms. This paradigm has created profound inequalities in who can build, deploy, and benefit from AI capabilities. Meanwhile, the global economy generates approximately 50 million metric tons of electronic waste annually, with laptops and personal computers representing a significant fraction of this environmental burden.

This article explores a fundamentally different approach: intentionally designed distributed AI networks running on repurposed laptop hardware. Far from being a mere technical curiosity, this paradigm represents a strategic reimagining of how AI infrastructure can be built, owned, and operated. When paired with federated learning architectures, renewable energy systems, and hardware-aware optimization, distributed laptop networks unlock extraordinary value across five critical dimensions:

- Extreme cost reduction by extracting computational value from hardware that would otherwise be discarded

- Direct e-waste mitigation by extending device lifespan and avoiding the carbon footprint of new server manufacturing

- Digital sovereignty and data localization for communities, institutions, and nations seeking independence from cloud oligopolies

- Contextual energy efficiency when powered by solar and battery storage in off-grid or unreliable-grid environments

- Educational value as a hands-on platform for learning distributed systems, federated learning, and resource-aware AI

This is not about competing with cloud providers on raw performance. Rather, it is about creating an entirely new category of AI infrastructure: one that is radically affordable, environmentally responsible, locally controlled, and globally accessible. The strategic opportunity lies in serving the billions of people and millions of organizations currently excluded from the AI revolution due to cost, connectivity, or sovereignty constraints.

Introduction: The AI Access Paradox

Artificial intelligence has become the defining technology of the 21st century, yet access to AI capabilities remains remarkably concentrated. The computational infrastructure required to train and deploy state-of-the-art models is predominantly controlled by a handful of hyperscale cloud providers and well-funded technology companies. For the vast majority of the world’s population, AI remains something that happens to them rather than something they can build, control, or fundamentally shape.

This concentration creates several interlocking problems. First, there is the cost barrier: cloud GPU instances can easily exceed thousands of dollars per month, making AI development prohibitively expensive for schools, small businesses, research institutions in developing countries, and community organizations. Second, there is the dependency trap: reliance on external cloud infrastructure means that data, models, and computational capabilities remain fundamentally outside local control. Third, there is the environmental contradiction: even as AI is positioned as a tool for solving climate challenges, the industry’s demand for purpose-built servers drives enormous manufacturing emissions and electronic waste generation.

Against this backdrop sits an often-overlooked resource: aging laptop computers. Corporate refresh cycles, educational institution upgrades, and consumer replacement patterns generate an enormous stream of functional hardware that is relegated to landfills or informal recycling channels despite retaining significant computational capability. A typical laptop from 2013-2015, powered by a 2nd or 3rd generation Intel Core i5 or i7 processor with 8GB of RAM and solid-state storage, represents hardware that would have been considered high-performance just a decade ago. These machines are perfectly capable of running modern AI inference workloads and participating in federated learning networks.

The vision explored in this article is to transform this latent computational capacity into a new category of AI infrastructure. Through intentionally designed distributed software, intelligent orchestration, and hardware-aware optimization, networks of repurposed laptops can become powerful platforms for local AI deployment. This approach does not require choosing between performance and sustainability, between local control and sophisticated capabilities, or between affordability and real-world impact. Instead, it creates a fundamentally different value proposition that serves needs and contexts that cloud infrastructure was never designed to address.

The Strategic Imperative: Why Distributed Laptop AI Networks Matter

1.1 Extreme Cost Reduction and Value Creation

The economic case for distributed laptop AI networks begins with a simple observation: the marginal cost of acquiring repurposed laptop hardware is dramatically lower than purchasing new server infrastructure. In many contexts, aging laptops can be obtained for free or at minimal cost from corporate donations, educational surplus, or e-waste streams. Even when purchased on secondary markets, devices that meet the minimum specifications for AI workloads typically cost between $50-150 per unit.

Consider the cost structure of building a modest AI inference cluster. A traditional approach might involve purchasing a dedicated server with modern CPUs or GPUs, with hardware costs easily exceeding $5,000-15,000 for a single machine. Cloud alternatives carry ongoing operational costs that accumulate indefinitely. In contrast, a distributed network of 5-8 repurposed laptops might represent a total hardware investment of $400-800, or potentially zero in donation-based scenarios.

This cost differential is not merely about cheaper hardware. It represents the creation of computational value from assets that the market has already written off. Every laptop diverted from the waste stream and integrated into an AI network represents computational capacity with effectively zero acquisition cost from a lifecycle perspective. The hardware has already been manufactured, its embedded carbon already emitted, its economic depreciation already completed. Reusing it for AI workloads extracts additional value without triggering any of the upstream environmental or economic costs associated with new production.

Moreover, the distributed nature of laptop networks creates unique economic advantages. Unlike monolithic servers that require full capacity investment upfront, laptop networks can scale incrementally. An organization can start with three donated machines, validate the approach, and gradually expand as additional hardware becomes available. This pay-as-you-grow model dramatically reduces both capital requirements and deployment risk.

The total cost of ownership calculation becomes even more favorable when operational expenses are considered. Modern laptops were designed for energy efficiency in battery-powered scenarios, with power management capabilities that allow them to idle at 9-15 watts and run typical AI inference workloads at 18-25 watts. When paired with solar and battery storage systems sized appropriately for the cluster, the ongoing energy costs can approach zero in sunny climates. This stands in stark contrast to both cloud services with their monthly recurring charges and on-premise servers with their substantial grid electricity consumption.

1.2 Direct E-Waste Mitigation and Environmental Justice

Electronic waste represents one of the fastest-growing waste streams globally, with laptop computers contributing significantly to this crisis. The typical lifecycle of a laptop in developed economies involves 3-5 years of active use followed by disposal, despite the hardware often retaining 60-80% of its original computational capability. This accelerated obsolescence is driven not by technical failure but by software requirements, organizational refresh policies, and market dynamics that prioritize new sales over extended use.

The environmental burden of this waste is profound. Laptops contain valuable materials like copper, aluminum, and rare earth elements, but they also contain hazardous substances including lead, mercury, and brominated flame retardants. When improperly recycled through informal channels, these materials contaminate soil and water, creating health hazards in communities that are often already environmentally vulnerable. Even formal recycling processes are energy-intensive and result in significant material losses.

Distributed laptop AI networks directly address this crisis by extending device lifespan and creating compelling new use cases for aging hardware. A laptop that might otherwise be discarded after 5 years of office use can serve an additional 3-5 years as a node in an AI cluster. This extension is particularly valuable because the hardware has already incurred its manufacturing carbon footprint: the energy-intensive processes of mining, refining, manufacturing, and global logistics have already occurred. Every additional year of productive use amortizes this embedded carbon over a longer operational lifetime, improving the environmental efficiency of the original investment.

The environmental comparison becomes even more favorable when we consider the avoided emissions from not manufacturing new servers. Modern server production is extraordinarily carbon-intensive, with estimates suggesting that manufacturing a typical server generates 2-4 tons of CO₂ equivalent before the device ever processes its first workload. By contrast, reusing existing laptop hardware avoids these manufacturing emissions entirely. The contextual energy efficiency argument is critical here: while an individual laptop may not match the pure operational efficiency of a modern server, the avoided manufacturing emissions can offset years of slightly higher operational energy consumption.

1.3 Digital Sovereignty and Data Localization

The concentration of AI capabilities in cloud infrastructure controlled by a handful of corporations creates fundamental dependencies that increasingly concern governments, institutions, and communities. When AI processing happens in distant data centers, questions of data sovereignty, privacy, and local control become acute. This is particularly problematic for applications involving sensitive information: healthcare records, agricultural data, educational assessments, civic infrastructure monitoring, and personal communications.

Distributed laptop AI networks offer a compelling alternative: computational infrastructure that is physically present, locally controlled, and architecturally designed for data localization. When a school deploys AI-powered educational assistants on a laptop cluster within its own premises, student data never traverses external networks or resides on third-party servers. When a rural clinic uses AI for diagnostic support, patient information remains within the health facility’s walls. When a municipality implements traffic analysis or environmental monitoring, the raw data stays within local systems.

This local control extends beyond mere data location to encompass genuine digital sovereignty. Organizations that own and operate their own AI infrastructure are not subject to cloud provider terms of service changes, pricing increases, or service discontinuations. They cannot be de-platformed or have their access arbitrarily restricted. The computational capabilities belong to them in a fundamental, physical sense. This independence is particularly valuable in geopolitically sensitive contexts or for organizations serving vulnerable populations.

Moreover, distributed architectures enable federated learning approaches where multiple organizations can collaboratively improve AI models without centralizing their data. A network of clinics can jointly train diagnostic models while keeping patient records entirely local. A group of agricultural cooperatives can build crop disease detection systems that learn from each farm’s data without ever pooling that data centrally. This federated approach combines the benefits of collaborative learning with the privacy guarantees and sovereignty protections of fully local deployment.

For nations and regions seeking to build AI capabilities independent of foreign technology dependencies, distributed laptop networks provide an accessible entry point. Rather than requiring massive capital investments to build data centers or develop indigenous chip manufacturing capabilities, governments can leverage existing hardware stocks and focus resources on software development, model training, and capacity building. This pragmatic path to digital sovereignty is particularly relevant for developing nations that face both constrained budgets and strategic imperatives for technological independence.

1.4 Contextual Energy Efficiency and Renewable Integration

The energy efficiency narrative around distributed laptop AI networks requires nuance. It is true that modern purpose-built servers achieve better performance-per-watt than aging laptop hardware when comparing pure operational efficiency. However, this narrow metric obscures several critical contextual factors that make laptop networks highly energy-efficient in real-world deployment scenarios.

First, as previously discussed, reusing existing hardware avoids the massive embedded energy cost of manufacturing new servers. When this manufacturing burden is amortized over the full lifecycle, repurposed laptops often demonstrate superior total energy efficiency even if their operational consumption is higher. Second, laptops were specifically designed for battery operation, which means they incorporate sophisticated power management capabilities that servers often lack. These features enable aggressive dynamic scaling, allowing nodes to reduce power consumption to 9-15 watts during idle periods and scale up to 30-45 watts only when actively processing workloads.

Third, and perhaps most significantly, the modest power requirements of laptop clusters make them exceptionally well-suited for renewable energy integration. Consider a typical deployment scenario: a 5-laptop cluster running AI inference workloads might average 150 watts during active periods and 70 watts during low-load operation. Such a system can be powered by a 400-500 watt solar panel array paired with a 1.5-2 kWh battery bank, creating a fully off-grid AI infrastructure with effectively zero ongoing energy costs.

This renewable integration creates profound opportunities in contexts where grid electricity is unreliable, expensive, or unavailable. Rural schools in sub-Saharan Africa, community centers in Southeast Asia, agricultural hubs in Latin America, and remote clinics across the Global South can deploy sophisticated AI capabilities without dependence on utility infrastructure. The same solar and battery systems that might power lights and basic electronics can also support AI-driven educational tools, diagnostic assistants, crop monitoring systems, and language translation services.

Environmental impact assessments comparing hybrid solar-battery-diesel systems with grid electrification consistently show 75-80% lower carbon emissions over 25-year lifecycles for the hybrid approach. When deployment timelines are considered (solar systems can be operational in months while grid extension may require years), the cumulative emissions advantage becomes even more pronounced. For distributed AI applications, this means that a laptop cluster powered by renewable energy can deliver both computational capabilities and climate benefits simultaneously, serving as a demonstration of sustainable digital infrastructure.

1.5 Educational Value and Capacity Building

Distributed laptop AI networks provide exceptional educational value that extends far beyond their immediate computational utility. The process of building, deploying, and maintaining such systems offers hands-on learning opportunities across multiple critical technology domains that are typically only accessible to students at elite institutions or professionals at well-resourced companies.

First, these systems provide concrete exposure to distributed systems architecture. Students and practitioners learn about coordinator-worker topologies, task scheduling, load balancing, fault tolerance, and cluster orchestration through direct engagement rather than abstract study. The heterogeneous nature of laptop hardware introduces real-world complexity that mirrors enterprise distributed systems: nodes with different capabilities, varying reliability characteristics, network latency considerations, and the need for sophisticated resource management.

Second, distributed laptop networks create ideal platforms for learning modern AI techniques in resource-constrained contexts. Students encounter the practical challenges of model selection, quantization, pruning, and hardware-aware optimization. They learn to evaluate trade-offs between model accuracy and computational efficiency, to profile workload performance across heterogeneous hardware, and to design AI applications that respect real-world constraints. This stands in contrast to conventional AI education that often assumes unlimited computational resources and glosses over deployment practicalities.

Third, federated learning implementations on laptop networks provide hands-on experience with privacy-preserving machine learning, differential privacy, secure aggregation, and collaborative model training. These skills are increasingly critical as privacy regulations proliferate and organizations seek to extract value from decentralized data sources. Students who build federated learning systems on laptop clusters develop practical expertise that is directly transferable to enterprise applications and research contexts.

The accessibility of laptop-based AI infrastructure is crucial for educational equity. A well-funded university might have access to GPU clusters for student projects, but a community college, vocational training center, or secondary school in a developing country typically does not. By enabling sophisticated AI education on repurposed hardware, distributed laptop networks democratize access to these learning experiences. Students can build genuine distributed AI systems regardless of their institution’s budget, gaining practical skills that position them for careers in technology and research.

Technical Architecture for Distributed Laptop AI Networks

2.1 Hardware Selection and Minimum Specifications

The foundation of any distributed laptop AI network is the hardware itself. While older laptops often vary considerably in capabilities, establishing practical minimum specifications ensures that clusters can deliver meaningful performance while maintaining reasonable operational costs.

Recommended minimum specifications:

- CPU: 64-bit x86-64 architecture, preferably Intel Core i5 or i7 (2nd generation or newer). Earlier Core 2 Duo processors can serve very lightweight roles but will bottleneck most AI workloads.

- RAM: 8GB minimum for meaningful AI inference. 4GB can handle very light workloads but will struggle with most practical applications. 16GB or more significantly expands capabilities.

- Storage: Solid-state drive (SSD) strongly recommended, minimum 128GB. SSDs dramatically improve model loading times, data access patterns, and overall system responsiveness. Traditional hard drives create severe bottlenecks.

- GPU (optional but valuable): Dedicated NVIDIA GPU with CUDA compute capability 3.0 or higher opens significant acceleration opportunities. Even older GPUs like the GeForce 610M can be useful, though support for very old hardware may be limited. Intel integrated graphics can support some OpenCL-based inference.

- Networking: Gigabit Ethernet preferred for reliable, high-throughput inter-node communication. WiFi introduces latency variability and reliability concerns but remains usable for less demanding applications.

A practical cluster might consist of 4-8 laptops meeting these specifications, with the most capable and reliable machine designated as the coordinator node. Hardware heterogeneity is not only acceptable but expected: distributed AI software can adapt workload distribution based on each node’s measured capabilities, allowing mixed-generation hardware to coexist productively.

2.2 Coordinator-Worker Architecture

Distributed laptop AI networks employ a coordinator-worker topology, also known as a master-worker or manager-agent architecture. This design pattern has proven effective for distributed systems across numerous domains and maps naturally to AI workload distribution.

The coordinator node serves as the cluster’s control plane with several critical responsibilities:

- Task scheduling and workload distribution based on node capabilities and current load

- Capability registry tracking each worker’s hardware profile, available runtimes, and performance characteristics

- Model registry managing available AI models, their resource requirements, and optimization artifacts

- Health monitoring and telemetry collection to detect failures and performance degradation

- Energy management coordinating power-aware scheduling and renewable energy integration

- API gateway providing external interfaces for job submission and cluster monitoring

Worker nodes function as the cluster’s compute plane, executing assigned tasks and reporting results. Worker design emphasizes resilience and adaptability: nodes should be stateless where possible, supporting hot addition and removal without cluster disruption. Workers degrade gracefully under resource pressure rather than failing catastrophically, using techniques like model quantization adjustment and batch size reduction to maintain operation even when memory or processing capacity is constrained.

For larger deployments or multi-site configurations, hierarchical federation allows multiple coordinator-worker clusters to collaborate. This topology supports use cases like a national educational system where individual schools operate local clusters that periodically federate for collaborative model training, or agricultural cooperatives where each farm maintains local inference capabilities while contributing to region-wide predictive models.

2.3 Orchestration and Container Infrastructure

Containerization provides essential abstraction for distributed laptop AI networks, enabling portable deployment of AI models and dependencies across heterogeneous hardware. Docker has emerged as the de facto standard for container packaging, with broad ecosystem support and extensive documentation.

For cluster orchestration, lightweight alternatives to Kubernetes are preferred given the resource constraints of laptop hardware. HashiCorp Nomad provides sophisticated job scheduling, resource allocation, and health checking with significantly lower overhead than Kubernetes. It supports both containerized and native workloads, handles mixed x86 and ARM architectures, and integrates well with service discovery and configuration management tools.

Docker Swarm represents another viable option, particularly for organizations seeking to minimize operational complexity. While less feature-rich than Nomad, Swarm provides adequate orchestration capabilities for many distributed AI scenarios with very straightforward deployment and management workflows.

Node labeling is critical for effective orchestration. Each worker should be tagged with metadata describing its hardware capabilities: CPU generation and core count, RAM capacity, GPU presence and model, storage type and capacity, and power profile (grid-powered versus solar-battery). The scheduler uses these labels to make intelligent placement decisions, routing GPU-accelerated workloads to nodes with appropriate hardware and steering memory-intensive tasks toward machines with ample RAM.

Cluster bootstrap is streamlined through infrastructure-as-code approaches using Ansible playbooks or similar automation tools. These scripts configure networking, install container runtimes, establish orchestration agents, and deploy monitoring infrastructure, transforming a collection of disparate laptops into a managed cluster within hours rather than days of manual configuration.

2.4 AI Model Execution Layer and Runtime Selection

Efficient AI model execution on heterogeneous laptop hardware requires a flexible runtime layer that can adapt to diverse processors, accelerators, and memory constraints. A pluggable architecture allows the system to select optimal runtimes based on each node’s capabilities.

Core runtime options include:

- ONNX Runtime: Cross-platform inference engine supporting a wide range of hardware. Excellent general-purpose choice for CPU-based inference with good optimization support.

- OpenVINO: Intel’s inference toolkit optimized for their processors and integrated GPUs. Delivers substantial performance improvements on Intel hardware through specialized instruction sets and neural network optimizations.

- TensorRT: NVIDIA’s inference optimizer for CUDA-capable GPUs. Essential for extracting maximum performance from older NVIDIA discrete graphics cards that might be present in some laptops.

- TensorFlow Lite: Lightweight runtime particularly well-suited for ARM processors and mobile-oriented hardware that might be present in some laptop configurations.

The coordinator’s capability registry maps each worker’s hardware profile to appropriate runtimes. When scheduling inference tasks, the coordinator selects workers not just based on availability but on runtime compatibility and expected performance. This hardware-aware scheduling ensures that Intel-optimized models run on Intel hardware, CUDA workloads route to GPU-equipped nodes, and ARM-specific optimizations are leveraged where available.

Models themselves are stored in the model registry in multiple formats and optimization levels. A given AI model might exist as a full-precision ONNX file for maximum accuracy, an INT8 quantized version for faster CPU inference, and a TensorRT-optimized variant for GPU execution. The runtime selection logic automatically chooses the most appropriate version based on the assigned worker’s capabilities, balancing accuracy requirements against performance constraints.

2.5 Federated Learning Architecture

Federated learning represents one of the most compelling applications for distributed laptop AI networks, enabling collaborative model training without centralizing sensitive data. Frameworks like Flower (Federated Learning Flower) and OpenFL (Open Federated Learning) provide production-ready implementations that can be adapted for laptop cluster deployments.

The federated learning workflow involves several key phases. During initialization, the coordinator distributes a base model to participating workers along with training configuration. Each worker then performs local training on its private dataset, computing model updates without ever sharing raw data externally. Workers send only the model parameter updates back to the coordinator, which aggregates these updates using algorithms like Federated Averaging to produce an improved global model. This updated model is redistributed to workers for the next round of local training.

Critical adaptations for laptop hardware include support for intermittent participation. Unlike data center federated learning where all nodes are continuously available, laptop networks must accommodate workers that may disconnect due to power constraints, network issues, or device mobility. The system tracks node availability patterns and adjusts aggregation strategies accordingly, using techniques like asynchronous aggregation and patience-based waiting to balance training progress against participation requirements.

Security and privacy considerations are paramount. Communication between workers and coordinator should use TLS encryption to protect model updates in transit. For particularly sensitive applications, differential privacy techniques can add calibrated noise to updates before aggregation, providing mathematical privacy guarantees. Secure aggregation protocols allow the coordinator to compute aggregate statistics without observing individual worker contributions, further strengthening privacy protections.

Multi-site federation extends this architecture to allow collaboration across geographically distributed laptop clusters. A regional health network might consist of multiple clinic clusters, each maintaining local patient data and performing local inference, but periodically participating in federated rounds to improve shared diagnostic models. This hierarchical federation provides both local autonomy and collective learning benefits.

2.6 Energy-Aware Orchestration and Solar Integration

Integrating distributed laptop AI networks with solar and battery storage systems requires sophisticated energy-aware orchestration that balances computational throughput against power availability and battery state of charge.

Power profiling establishes baseline understanding of cluster energy consumption. Each node’s power draw is measured across different operational states: idle, light inference, heavy CPU load, and GPU utilization where applicable. This profiling data informs scheduling decisions, allowing the coordinator to estimate the power cost of assigning particular workloads to specific nodes.

The energy management system monitors solar generation and battery state through integration with charge controllers and battery management systems. During periods of strong solar generation with high battery charge, the coordinator can schedule computationally intensive workloads and opportunistic tasks like model optimization and federated learning rounds. As battery levels decline or solar input decreases, the system shifts toward more energy-efficient operation: pausing non-critical workloads, reducing active node count, and prioritizing essential inference services.

Duty cycling strategies allow clusters to maintain core functionality while conserving energy during extended periods of cloud cover or high usage. A minimal operational mode might keep only the coordinator and 1-2 worker nodes active for essential inference requests, bringing additional nodes online only when power conditions improve or workload urgency demands it. This graceful degradation ensures that critical AI services remain available even under energy constraints while avoiding complete system shutdown.

Sizing solar and battery systems for laptop AI clusters is straightforward given the modest power requirements. A typical 5-laptop cluster averaging 150 watts during active periods can be powered by 400-500 watts of solar panels and a 1.5-2 kWh battery bank, providing reliable 24-hour operation in most sunny climates with one day of autonomy for cloudy conditions. This relatively small renewable energy system is orders of magnitude more accessible than what would be required to power equivalent data center infrastructure.

Novel Applications and Use Cases

3.1 Education: AI-Powered Learning in Resource-Constrained Settings

Educational institutions represent ideal deployment environments for distributed laptop AI networks. Schools frequently have access to aging computer hardware from previous technology refresh cycles and face budget constraints that make cloud AI services prohibitively expensive. Moreover, educational data privacy concerns create strong incentives for local processing.

A distributed laptop cluster running compact natural language processing models can power intelligent tutoring systems, automated essay feedback, and multilingual translation services. Students interact with AI assistants that run entirely on local infrastructure, ensuring that learning data and interaction histories remain within the school’s control. The same cluster can support computer vision applications for automated attendance, learning activity recognition in classrooms, and accessibility features like real-time sign language translation.

Federated learning enables remarkable collaborative possibilities across school districts or national education systems. Individual schools maintain local clusters for daily AI services while periodically participating in federated rounds to improve shared models. A literacy assessment tool might be trained collaboratively across hundreds of schools, learning from diverse student populations and pedagogical approaches without ever centralizing sensitive student data. This approach provides state-of-the-art AI capabilities while preserving privacy and local autonomy.

3.2 Healthcare: Local Diagnostic Support and Privacy-Preserving Research

Healthcare applications demonstrate both the power and necessity of local AI deployment. Medical data is among the most sensitive information categories, subject to strict regulations like HIPAA, GDPR, and local privacy laws. Rural clinics and regional health facilities often lack the resources for expensive cloud AI services but desperately need diagnostic support tools.

A laptop cluster running compact vision models can provide diagnostic assistance for common conditions: analyzing X-rays for signs of tuberculosis or pneumonia, examining retinal images for diabetic retinopathy, evaluating skin lesion photographs for melanoma risk. These AI-powered screening tools extend the capabilities of healthcare workers in resource-limited settings, flagging cases that require specialist review while handling routine assessments locally.

Natural language models enable clinical documentation assistance, medical coding support, and patient communication tools in local languages. A clinic serving a multilingual community can deploy translation and transcription services that process patient-provider conversations without sending audio to external servers.

Federated learning across a network of health facilities creates unique opportunities for collaborative medical AI development. Multiple clinics can jointly train diagnostic models that learn from diverse patient populations and clinical contexts without ever pooling patient records centrally. This approach addresses the data scarcity challenges that often limit medical AI development while providing robust privacy protections. A regional health network might collaboratively develop models for local disease patterns, endemic conditions, or population-specific health risks that commercial AI tools trained on global datasets would miss.

3.3 Agriculture: Precision Farming with Local AI

Agricultural applications of distributed laptop AI networks address critical food security challenges while respecting the operational realities of farming communities. Computer vision models for crop disease detection, pest identification, and growth stage monitoring can run on local hardware, providing farmers with instant diagnostic support without relying on cloud connectivity that may be unavailable in rural areas.

A laptop cluster at a cooperative processing center or extension service office can analyze images from farmers’ smartphones, identifying disease symptoms, nutrient deficiencies, or pest infestations with recommendations for intervention. Time-series models process weather data, soil sensor readings, and historical yield information to generate localized planting recommendations and irrigation schedules optimized for micro-climate conditions.

Federated learning across farming cooperatives creates powerful collective intelligence while preserving each farm’s proprietary data. Agricultural knowledge embedded in planting decisions, pest management strategies, and yield outcomes can inform collaborative models without exposing individual farm operations to competitors or external organizations. Regional crop disease prediction models learn from distributed observations across many farms, providing early warning systems that benefit entire agricultural communities.

3.4 Civic Technology: Local Governance and Community Services

Municipal governments and community organizations can leverage distributed laptop AI networks for diverse civic applications. Traffic analysis and vehicle counting support transportation planning without streaming video to external servers. Environmental monitoring analyzes air quality sensor data, noise pollution patterns, and waste management logistics through local processing.

Natural language processing supports citizen services through multilingual chatbots that answer common questions about permits, services, and procedures. Document processing automates form classification, application review, and records management. Speech-to-text transcription makes public meeting minutes accessible without manual transcription costs.

The local deployment model aligns particularly well with digital sovereignty principles increasingly important to local governments. Municipalities can deploy AI-powered services without creating dependencies on technology companies or exposing citizen data to third-party processing. This independence becomes especially valuable for applications involving surveillance, law enforcement support, or social services where data protection and public accountability are paramount.

3.5 Research and Experimentation: Democratizing AI Development

Distributed laptop AI networks provide invaluable platforms for research and experimentation, particularly for institutions and researchers without access to expensive computational infrastructure. Graduate students, independent researchers, and scientists at under-resourced institutions can conduct meaningful AI research on distributed systems built from donated or repurposed hardware.

Federated learning research particularly benefits from accessible testbeds. Investigating new aggregation algorithms, privacy-preserving techniques, handling non-IID data distributions, and developing resilient training protocols all require distributed infrastructure that laptop clusters can provide without massive capital investment.

Beyond academic research, these systems enable grassroots AI innovation. Community organizations can experiment with AI solutions to local challenges: language preservation through speech recognition models, cultural heritage digitization through computer vision, indigenous knowledge systems integration through natural language processing. By removing cost barriers to computational infrastructure, distributed laptop networks democratize participation in AI development, expanding who can build, deploy, and benefit from these technologies.

SWOT Analysis: Distributed Laptop AI Networks

| STRENGTHS | OPPORTUNITIES |

| • Extreme cost reduction through e-waste valorization • Direct environmental impact via extended hardware lifespan • Avoided manufacturing emissions from new server production • Digital sovereignty and complete data localization • Independence from cloud service dependencies • Excellent renewable energy integration potential • Incremental scalability with minimal capital requirements • Rich educational value across multiple domains • Natural fit for federated learning architectures • Privacy-preserving by design | • Massive underserved market in education, healthcare, agriculture • Growing demand for digital sovereignty solutions • Increasing e-waste crisis creates hardware availability • Declining costs of solar and battery storage systems • Privacy regulations strengthening local deployment case • Potential for government and NGO funding for sustainable tech • Corporate ESG initiatives creating hardware donation streams • Edge AI market growth validating distributed architectures • Open-source AI ecosystem providing excellent foundation • Community-building and capacity development opportunities |

| WEAKNESSES | THREATS |

| • Lower operational efficiency than modern server hardware • Hardware heterogeneity creates management complexity • Higher failure rates with aging components • Sophisticated software layer required for effectiveness • Limited to inference and lightweight training workloads • Network bandwidth constraints in rural deployments • Requires technical expertise for deployment and maintenance • Initial setup investment despite low hardware costs • Quality variation in donated hardware sources • Battery degradation in laptop hardware stock | • Cloud providers may offer aggressive pricing for developing markets • Perception challenges around ‘e-waste’ infrastructure quality • Rapid AI model size inflation reducing hardware suitability • Ecosystem fragmentation in distributed AI tooling • Limited vendor support for aging hardware • Potential regulatory barriers for critical applications • Competition from purpose-built edge AI hardware • Supply chain disruptions affecting hardware availability • Cybersecurity concerns with heterogeneous systems • Institutional inertia favoring established cloud solutions |

The SWOT analysis reveals that distributed laptop AI networks occupy a distinct strategic position rather than competing directly with traditional cloud or data center infrastructure. The approach’s core strengths—cost reduction, environmental benefits, sovereignty, and renewable integration—align precisely with opportunities in underserved markets facing privacy concerns and sustainability imperatives. While weaknesses around operational efficiency and complexity are real, they are manageable through appropriate software design and realistic workload targeting. Threats primarily come from perception and ecosystem maturity rather than fundamental technical limitations.

Business Case: Economic and Strategic Viability

5.1 Total Cost of Ownership Analysis

A comprehensive total cost of ownership comparison demonstrates the economic advantages of distributed laptop AI networks across multiple deployment scenarios. Consider a typical use case: a regional educational authority seeking to deploy AI-powered tutoring and administrative automation across 50 schools.

Cloud deployment scenario:

- Monthly cloud GPU instance costs: $800-1,500 per instance

- API calling costs for inference: $200-400 per month for moderate usage

- Data egress and storage: $150-300 per month

- Annual cost: $15,000-26,000 ongoing, escalating with usage

Distributed laptop network scenario:

- Hardware acquisition: $3,000-5,000 for 50 laptops at $60-100 each (or $0 if donated)

- Initial software development/integration: $8,000-15,000 one-time

- Solar and battery systems: $6,000-10,000 for renewable energy integration

- Annual electricity (grid backup): $500-800

- Maintenance and replacement: $1,000-2,000 annually

- Total first-year cost: $18,500-32,800; subsequent years: $1,500-2,800

The distributed approach achieves cost parity with cloud deployment within 1-2 years despite higher initial investment, then dramatically outperforms on ongoing costs. Over a five-year planning horizon, the laptop network’s total cost of $26,000-42,000 compares favorably to cloud costs of $75,000-130,000, representing 65-68% cost savings.

These calculations assume purchased hardware. In scenarios where aging laptops are donated by corporations, governments, or NGOs conducting technology refreshes, hardware acquisition costs approach zero, improving economics dramatically. The cost advantage becomes even more pronounced in regions where cloud service pricing is higher due to limited local data center presence or unfavorable currency exchange rates.

5.2 Environmental Return on Investment

The environmental case for distributed laptop AI networks extends beyond simple e-waste diversion to encompass lifecycle carbon accounting, circular economy principles, and avoided environmental externalities.

Manufacturing a typical enterprise server generates approximately 2,000-4,000 kg CO₂e in embedded emissions before the device processes any workloads. This includes mining of raw materials, component manufacturing, assembly, and global logistics. A repurposed laptop has already incurred these manufacturing emissions in its initial lifecycle; reusing it for AI workloads avoids triggering any additional manufacturing carbon burden.

When powered by renewable energy, the operational carbon footprint of laptop networks approaches zero. A solar-powered cluster emits approximately 140 gCO₂e/kWh when accounting for solar panel and battery manufacturing amortized over system lifetime, compared to 808 gCO₂e/kWh for grid electricity with diesel backup in many developing regions. Over 25 years, this difference amounts to 31,632 kg CO₂ avoided—equivalent to taking 7 cars off the road for a year.

Beyond carbon metrics, distributed laptop networks reduce water consumption (minimal compared to data center cooling requirements), eliminate transmission corridor land use impacts, and preserve biodiversity by avoiding new infrastructure development in greenfield sites. The circularity benefits are substantial: extending laptop lifespans from 5 to 8-10 years through AI reuse reduces the frequency of replacement cycles, decreasing demand for new production and associated resource extraction.

Organizations facing environmental, social, and governance (ESG) reporting requirements or carbon reduction commitments can quantify these benefits as measurable impacts. Corporate hardware donors can claim extended product lifecycle metrics and avoided emissions. Deploying institutions can report renewable energy adoption, e-waste reduction, and avoided cloud carbon footprints. These environmental returns complement financial savings, creating compounding value propositions.

5.3 Strategic Value and Competitive Positioning

The strategic value of distributed laptop AI networks extends beyond quantifiable financial and environmental metrics to encompass competitive positioning, organizational capabilities, and market differentiation.

For educational institutions, local AI infrastructure creates differentiation in increasingly competitive markets. Universities and vocational schools can market hands-on experience with distributed AI systems as a unique offering that prepares students for emerging career opportunities. Research institutions gain experimental platforms that don’t require grant funding for cloud computing, democratizing access to AI research infrastructure.

Healthcare organizations achieve strategic advantages through data sovereignty and privacy compliance. The ability to deploy sophisticated AI diagnostic tools while maintaining absolute control over patient data creates competitive positioning in privacy-conscious markets and differentiation from competitors dependent on cloud services with potential data exposure risks.

For technology service providers and social enterprises, distributed laptop AI networks represent addressable market opportunities in the Global South where traditional cloud economics don’t work. Organizations can build sustainable business models around system integration, software development, maintenance services, and federated learning coordination for networks of laptop clusters across schools, clinics, and community organizations.

National governments and regional authorities pursuing digital sovereignty objectives gain pragmatic pathways to AI capability development without massive capital investments or dependencies on foreign technology providers. The incremental, learn-by-doing approach to building distributed AI infrastructure supports capacity building while delivering immediate practical value.

Corporate hardware donors realize strategic ESG value through extended producer responsibility initiatives. Rather than simply recycling aging IT assets, companies can facilitate their redeployment for social good applications while claiming circular economy metrics and community impact. These initiatives strengthen corporate reputation, employee engagement, and stakeholder relationships while reducing disposal costs.

5.4 Risk Mitigation and Resilience

Distributed laptop AI networks provide important risk mitigation benefits that complement financial and strategic advantages. The dependency risks inherent in cloud-based AI infrastructure—vendor lock-in, service discontinuations, pricing changes, geopolitical disruptions—are substantially reduced through local ownership and control.

Organizations operating in regions with unreliable internet connectivity gain resilience through local processing. AI services continue functioning during network outages that would completely disable cloud-dependent systems. This resilience is particularly valuable for critical applications in healthcare, agriculture, and civic services where service continuity can have significant real-world consequences.

The distributed architecture itself provides redundancy benefits. Unlike centralized systems where a single point of failure can disable all services, laptop networks degrade gracefully as individual nodes fail. Core functionality continues on remaining nodes while failed units are repaired or replaced, minimizing service disruptions.

Data breach risks are fundamentally different in local deployment scenarios. While distributed systems require robust security practices, the attack surface is limited to local network access rather than internet-exposed cloud services. For applications involving highly sensitive data, this architectural difference can be decisive in risk assessment and compliance frameworks.

5.5 Implementation Roadmap and Success Factors

Successful deployment of distributed laptop AI networks requires structured implementation approaches that address both technical and organizational dimensions. A phased rollout strategy minimizes risk while demonstrating value early in the process.

Phase 1: Pilot and Validation (Months 1-3)

- Assemble initial 3-5 laptop cluster with hardware meeting minimum specifications

- Deploy baseline orchestration and container infrastructure

- Implement 1-2 high-value AI applications with clear success metrics

- Profile workload performance and energy consumption

- Validate cost and capability assumptions

Phase 2: Scale and Integration (Months 4-6)

- Expand cluster to 8-12 nodes based on validated workload requirements

- Implement production monitoring, alerting, and maintenance procedures

- Deploy additional AI applications addressing priority use cases

- Integrate renewable energy systems if planned

- Develop operational runbooks and knowledge transfer materials

Phase 3: Optimization and Federation (Months 7-12)

- Implement advanced features like federated learning where applicable

- Optimize model selection and quantization based on operational data

- Deploy energy-aware orchestration and renewable integration

- Establish connections with peer organizations for federated learning

- Document lessons learned and develop scaling playbooks

Critical success factors include executive sponsorship ensuring organizational commitment, technical champions with distributed systems expertise, clear use case definition with measurable outcomes, realistic expectation setting around capabilities and limitations, and investment in capacity building so local teams can maintain and evolve systems over time.

Organizations should prioritize applications where local deployment advantages are most pronounced: sensitive data processing requiring privacy protection, offline or intermittent connectivity scenarios, sovereignty requirements for critical infrastructure, and educational use cases where hands-on system access creates value beyond mere computational output.

Conclusion: Toward a Democratized AI Future

The vision of distributed AI networks running on repurposed laptop hardware represents far more than a technical architecture or cost optimization strategy. It articulates a fundamentally different model for who can build, deploy, and benefit from artificial intelligence—one that challenges the concentration of AI capabilities in hyperscale infrastructure and offers pragmatic pathways to digital sovereignty, environmental responsibility, and universal access.

The strategic advantages are multifaceted and mutually reinforcing. Extreme cost reduction through e-waste valorization makes AI infrastructure accessible to organizations and communities with minimal budgets. Direct environmental benefits from extended hardware lifespans and avoided manufacturing emissions align AI deployment with climate objectives rather than undermining them. Digital sovereignty and data localization provide independence from cloud oligopolies while respecting privacy regulations and cultural values. Renewable energy integration demonstrates that sustainable and sophisticated computational capabilities can coexist. Educational value democratizes learning opportunities across resource contexts.

These advantages create compelling business cases across education, healthcare, agriculture, civic technology, and research domains. The economic analysis consistently demonstrates 65-70% cost savings over cloud alternatives across five-year planning horizons, with even more favorable comparisons when hardware is donated rather than purchased. Environmental returns include multi-ton carbon avoidance through manufacturing emissions elimination and renewable energy operation. Strategic value encompasses competitive differentiation, organizational capability building, and market positioning in underserved segments.

The technical architecture required to realize this vision is increasingly mature. Container orchestration platforms like Nomad and Docker Swarm provide lightweight cluster management. Pluggable AI runtimes including ONNX Runtime, OpenVINO, and TensorRT deliver hardware-aware optimization across heterogeneous processors. Federated learning frameworks like Flower enable privacy-preserving collaborative training. Energy-aware orchestration allows sophisticated renewable integration. These components can be composed into production-ready systems that transform collections of aging laptops into capable AI platforms.

Challenges remain, certainly. Hardware heterogeneity creates management complexity. Aging components fail more frequently than new equipment. Sophisticated software development is required to abstract away infrastructure diversity. Operational efficiency lags purpose-built servers in pure performance-per-watt comparisons. But these are challenges of engineering and deployment rather than fundamental limitations. They represent opportunities for innovation rather than insurmountable barriers.

The broader implications extend beyond individual deployments to systemic transformation of AI accessibility. When schools in sub-Saharan Africa can deploy sophisticated AI-powered educational tools on donated hardware and solar panels, when rural clinics in Southeast Asia can offer diagnostic AI without cloud subscriptions, when agricultural cooperatives in Latin America can build crop intelligence through federated learning, when community organizations worldwide can experiment with AI solutions to local challenges—the geography of AI development begins to shift.

This democratization matters not just for equity but for innovation itself. AI systems trained exclusively on data from wealthy nations, developed by teams from privileged backgrounds, deployed in contexts of abundant resources—these systems encode particular worldviews and optimize for particular values. Broadening participation in AI development to include diverse communities, contexts, and constraints enriches the technology itself, surfacing use cases and approaches that homogeneous development communities would never discover.

The e-waste crisis that motivates this approach simultaneously represents urgent environmental challenge and extraordinary opportunity. The 50 million metric tons of electronic waste generated annually includes vast quantities of functional computational hardware discarded due to refresh cycles, software obsolescence, or market dynamics rather than physical failure. This waste stream will only grow as device replacement accelerates and computing proliferates. Transforming even a fraction of this flow from environmental burden to productive resource would represent meaningful progress on both sustainability and digital inclusion dimensions.

The declining costs of renewable energy create perfect timing for this convergence. Solar panels and battery storage have reached price points where powering modest laptop clusters becomes economically viable even in resource-constrained contexts. As these technologies continue improving, the renewable integration story strengthens further, potentially reaching points where distributed laptop AI networks demonstrate better total lifecycle environmental performance than even the most efficient purpose-built data centers operating on grid power.

Looking forward, several developments would accelerate adoption and impact. Standardized software distributions packaging orchestration, AI runtimes, and federated learning frameworks into turnkey deployments would lower technical barriers. Hardware donation programs connecting corporate refresh cycles with institutional needs would scale hardware availability. Funding mechanisms from governments, foundations, and development organizations recognizing distributed laptop AI networks as valid infrastructure investments would support broader deployment. Technical assistance networks providing deployment and optimization expertise would build local capacity.

The research community has important roles in advancing this paradigm. Continued development of efficient AI models suitable for resource-constrained hardware expands application possibilities. Federated learning algorithms robust to heterogeneous hardware and intermittent connectivity strengthen collaborative training capabilities. Energy-aware scheduling strategies optimize renewable integration. Privacy-preserving techniques enable sensitive applications. Hardware-aware optimization automatically adapts models to diverse processors.

But perhaps most importantly, this vision requires imagination and willingness to question assumptions about what AI infrastructure must look like. The concentration of AI in hyperscale data centers is not inevitable but rather reflects particular economic incentives, technological paths, and power distributions. Alternative models are possible—models that prioritize accessibility over raw performance, sovereignty over convenience, sustainability over growth, and participation over efficiency.

Distributed AI networks running on repurposed laptop hardware, powered by renewable energy, owned and operated by the communities and institutions they serve, connected through federated learning to build collective intelligence while preserving local autonomy—this represents one such alternative. It is a vision grounded in practical technology, demonstrated through working deployments, validated by economic analysis, and aligned with urgent environmental and social imperatives. Most fundamentally, it is a vision that expands who gets to participate in shaping the AI-driven future, ensuring that these transformative technologies serve humanity broadly rather than concentrating benefits among the already powerful. That democratic promise may be the most revolutionary dimension of all.