Preamble: The Virtual United Nations

Context and Purpose

We stand at a pivotal moment in human history. The challenges we face climate destabilization, pandemics, mass displacement, economic inequality, and the erosion of democratic norms are global in scope, interconnected in nature, and accelerating in speed. Yet the institutions designed to coordinate our collective response remain constrained by twentieth-century assumptions: that governance happens in physical spaces, that participation requires geographic proximity, that legitimacy flows exclusively through state representatives, and that decisions can unfold at a diplomatic pace.

These assumptions no longer hold.

More than 5 billion people now carry internet-connected devices. Digital platforms have demonstrated the possibility of coordinating action across borders, languages, and time zones at unprecedented scale. Citizens, particularly youth, demand direct participation in decisions that shape their futures. Meanwhile, the machinery of international cooperation built for a world of 51 nations in 1945 struggles to respond with the agility, inclusivity, and transparency that our interconnected crises demand.

The Opportunity

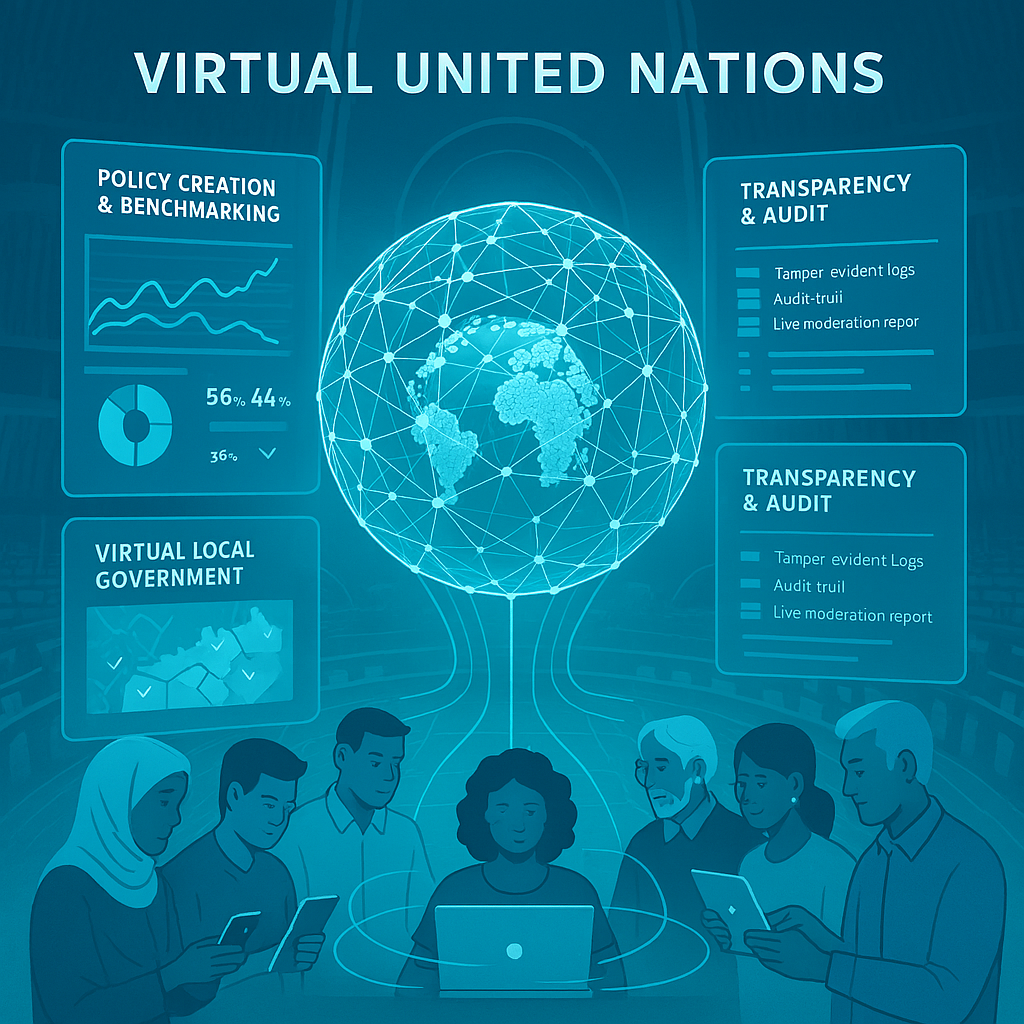

This document proposes a Virtual United Nations (V-UN) not as a replacement for existing international institutions, but as their necessary evolution into the digital age. The V-UN represents a fundamental rethinking of how global governance can operate: as an always-on, participatory, transparent, and mobile-first platform that extends the United Nations’ founding mission into the reality of the 21st century.

This is not a utopian vision. It is a structured proposal grounded in proven digital transformation practices, stakeholder-centered design, and defensive governance architecture. Drawing from enterprise requirements methodologies, security frameworks, and the lessons of both successful and failed digital governance experiments, this document articulates the value proposition, scope, stakeholder needs, implementation pathway, and critical risk mitigations necessary to make a Virtual UN viable.

What This Document Provides

Readers will find:

- A clear value proposition explaining why digital evolution of global governance is both necessary and achievable now

- Structured stakeholder analysis identifying who benefits, what they need, and how features trace back to real requirements

- Mobile-first and social media strategies recognizing that governance without mobile reach is structurally exclusionary

- The case for Virtual National Governments as necessary complements to global digital coordination

- Defensive governance design with specific controls against capture by states, corporations, or powerful individuals

- Practical ownership, funding, and transparency models that prioritize independence and resilience

- Implementation pathways that emphasize testing, learning, and phased scaling

Who Should Read This

This document is intended for:

- Policymakers and diplomats seeking to understand how digital transformation can enhance international cooperation

- Civil society organizations and NGOs advocating for more inclusive global decision-making

- Technology leaders and platform designers interested in governance infrastructure at scale

- Citizens and youth activists demanding meaningful participation in global affairs

- Researchers and academics studying digital governance, international relations, and institutional innovation

- Funders and philanthropic organizations evaluating investments in global public goods

How to Approach This Proposal

The Virtual UN concept operates at the intersection of technology, governance, and social change each a domain of high uncertainty. This document therefore employs inference discipline: distinguishing between what we know, what we can reasonably estimate, and what remains genuinely uncertain. Where assumptions are made, they are stated explicitly. Where gaps exist, they are categorized and flagged for testing.

The recommendation throughout is test before scale begin with pilot implementations in non-binding policy domains, measure actual adoption and attempted capture, learn from what works and what fails, then expand systematically.

The Stakes

The alternative to evolving our governance institutions is not maintaining the status quo it is watching them become increasingly irrelevant as coordination happens through informal networks, corporate platforms, and ad-hoc coalitions. The question is not whether global governance will go digital, but whether it will do so in ways that preserve democratic values, resist capture, and serve the many rather than the few.

This document is an invitation to imagine and then build that better path forward.

Related Resources: Virtual UN

Supporting documentation includes detailed software requirements, stakeholder analysis, risk assessment, and mapping of existing UN capabilities to virtual implementation.

| File Name | Short Description |

| Contrarian View and risk analysis.docx | Risk, friction, and mitigation analysis for the Virtual-UN, including contrarian critiques and failure scenarios. |

| Software Requirements Specification.docx | Detailed technical requirements for the Virtual-UN platform, covering functional and non-functional specs, architecture, and implementation phases. |

| UN deliverables.docx | Catalog of existing UN outputs, mapped to Type I Civilization domains, with recommendations for a virtual UN design. |

| stakeholder.docx | Stakeholder analysis identifying needs, pain points, and solution features for the Virtual-UN ecosystem. |

Status:

This is a working proposal. Feedback, critique, and collaboration are welcomed as essential parts of refining and testing these ideas.

Introduction

The Virtual United Nations (V-UN) is a next-generation governance concept that extends the mission of the United Nations into a fully digital, participatory, and globally accessible platform. Drawing on principles of digital transformation, stakeholder-centric design, and mobile-first engagement, the V-UN is designed to address modern global challenges climate change, inequality, digital rights, pandemics, and cross-border coordination at the speed and scale required in the 21st century.

This article integrates structured requirements-thinking (stakeholder mapping, traceability, scope definition) inspired by enterprise Business Requirements Documents (BRDs) to articulate the value, impact, scope, stakeholders, features, and go-to-market strategies of a Virtual UN, while also explaining why virtual national governments are a necessary complement in the digital era.

1. The Core Value Proposition of a Virtual UN

1.1 Why a Virtual UN Now?

Global governance today faces four structural constraints:

- Speed mismatch between crises and decision-making cycles

- Limited participation of citizens, youth, and marginalized groups

- Fragmented data and coordination across nations and agencies

- Physical dependency on diplomatic presence and in-person forums

The Virtual UN addresses these by providing:

- Always-on digital diplomacy and coordination

- Scalable, multilingual citizen participation

- Real-time data-sharing and policy simulation

- Lower-cost, lower-barrier access for developing nations

1.2 Value Created (Multi-Dimensional)

| Dimension | Value Delivered |

| Political | Inclusive global dialogue beyond state elites |

| Economic | Reduced cost of diplomacy, faster aid coordination |

| Social | Youth, diaspora, and civil society participation |

| Technological | Standardized digital governance infrastructure |

| Trust | Transparent processes, traceable decisions |

2. Scope and Functional Boundaries

2.1 In-Scope Capabilities

- Virtual General Assembly & Committees

- Digital policy drafting, voting, and consultation

- Global issue dashboards (climate, health, migration)

- Secure identity and credential verification

- Integration with national digital government systems

2.2 Out-of-Scope (Initial Phases)

- Enforcement of binding international law

- Replacement of sovereign governments

- Military or security command functions

This clear scope definition prevents mission creep and aligns with best-practice governance design.

3. Stakeholder Identification & Needs

3.1 Primary Stakeholders

| Stakeholder Group | Needs | Value from V-UN |

| Member States | Faster coordination, visibility | Reduced friction, data-driven diplomacy |

| Citizens & Youth | Voice, transparency | Direct participation, civic trust |

| NGOs & Civil Society | Access, legitimacy | Formal consultation channels |

| UN Agencies | Data integration | Unified digital backbone |

| Private Sector | Policy clarity | Predictable global frameworks |

| Academia & Think Tanks | Evidence-based policy | Policy labs & simulations |

3.2 Stakeholder-to-Feature Traceability

- Citizen need → Participatory platforms & mobile access

- State need → Secure negotiation and coordination tools

- Agency need → Interoperable data and reporting systems

This traceability ensures that every feature is justified by a real stakeholder requirement.

4. Social Media & Mobile-First Strategy

4.1 Why Social and Mobile Matter

Over 70% of the world’s population accesses the internet primarily via mobile devices. Governance without mobile reach is structurally exclusionary.

4.2 Social Media Strategy

Objectives

- Awareness of global issues

- Civic education and dialogue

- Rapid feedback and sentiment sensing

Channels

- Short-form video for policy explainers

- Live-streamed assemblies and debates

- Community moderation and multilingual outreach

Outcomes

- Increased youth engagement

- Real-time global sentiment insights

- Higher legitimacy through visibility

4.3 Mobile Platform Strategy

Core Mobile Features

- Digital ID & secure login

- Micro-consultations and polls

- Push notifications for global events

- Crisis alerts and participation calls

This transforms governance from a distant institution into a daily civic interface.

5. The Case for Virtual National Governments

5.1 Why Virtual Governments Are Needed

A Virtual UN is most effective when paired with Virtual National Governments (VNGs)—digital extensions of sovereign states that:

- Offer digital citizenship services

- Enable cross-border participation (diaspora, refugees)

- Interoperate with global platforms like the V-UN

5.2 V-UN + VNG Ecosystem

| Level | Role |

| Virtual National Government | Local execution & citizen services |

| Virtual UN | Global coordination & norms |

| Citizens | Active digital participants |

This layered model mirrors how the internet scaled: local nodes connected to global protocols.

6. Impact Assessment (RDC Lens)

Inference Justified: High novelty, high uncertainty, systemic risk.

Gap Analysis (5 Types Only)

- Capability: Digital literacy gaps (KU)

- Dependency: Reliance on national digital IDs (KK)

- Economic: Uneven funding capacity (KU)

- Regulatory: Data sovereignty & privacy conflicts (UU)

- Behavioral: Trust and adoption resistance (KU)

Impact Range (Illustrative)

- Participation increase: 2×–5× over traditional forums

- Cost reduction in diplomacy: 30–60%

- Policy feedback cycles: Weeks → Days

7. Implementation Pathway

Phased Approach

- Pilot – Limited issues, volunteer states, youth councils

- Expansion – Agency integration, mobile apps, social reach

- Institutionalization – Formal recognition, interoperability standards

Recommendation

Test – Begin with non-binding policy domains (climate, education, health) before scaling.

8. Risk, ownership and independence

Below is a defensive governance design for a Virtual UN / Virtual National Government ecosystem that minimizes subversion, capture, and corruption by governments, powerful individuals, and corporations—plus practical options for ownership, funding, and visibility/oversight.

1) Threat model: how capture actually happens

Capture usually doesn’t look like “a hostile takeover.” It shows up as:

- Funding leverage: “We pay the bills, so we set priorities.”

- Gatekeeping: controlling identity, access, moderation, or credentials.

- Regulatory choke points: hosting, payment rails, app stores, telecoms.

- Information advantage: closed audits, opaque algorithms, selective data access.

- Governance creep: emergency powers that become permanent.

- Staffing + procurement influence: insiders, revolving-door vendors, sweetheart contracts.

- Narrative warfare: coordinated disinfo to delegitimize opponents or steer outcomes.

So your defense has to be structural, not just “good policies.”

2) Design principles to prevent subversion & capture

A. “No single key can open the system”

Goal: no actor (state, CEO, billionaire, admin) can unilaterally:

- change rules

- censor records

- redirect funds

- alter votes

- silence watchdogs

How: split power across independent bodies + technical controls (multi-sig, quorum thresholds, independent auditors, and “public receipts”).

B. Radical traceability (but privacy-safe)

Make it easy to answer:

- Who decided what? When? Based on which inputs? With what conflicts?

This is straight out of enterprise traceability thinking: decisions must be auditable end-to-end (needs → policy drafts → votes → implementation). (This aligns with the stakeholder/traceability logic in your BRD-style approach. )

C. Make capture expensive and slow

If an attacker must corrupt 5+ independent layers over time, you’ve already raised the bar above most real-world capture attempts.

3) Concrete anti-capture controls (the “hard parts”)

3.1 Governance architecture (separation of powers)

Use a three-chamber model (simple, legible, resilient):

- Member-State Chamber (MSC)

- traditional UN-style participation

- Citizen & Civil Society Chamber (CSC)

- vetted NGOs, diaspora representation, youth councils, expert networks

- Independent Oversight Chamber (IOC)

- auditors, ombuds office, security council (technical), ethics board, judiciary-style review

Rule: major governance changes require supermajority across all chambers, not just one.

3.2 Constitutional constraints (rules that are hard to change)

Create a short “Digital Constitution” that locks in:

- non-discrimination rules

- transparency minimums

- audit rights

- term limits

- emergency powers limits (time-bound + renewal requires multi-chamber approval)

- data rights (privacy, portability, minimal retention)

- anti-capture clauses (conflict-of-interest, funding caps, procurement rules)

3.3 Identity, access, and anti-impersonation (without enabling surveillance)

Big risk: if governments control identity, they can silence or impersonate.

Design option: “Plural Identity”

- Users can verify through multiple routes:

- national ID (where safe)

- reputable NGOs / universities / professional bodies

- UN-issued credentials for refugees/stateless individuals

- No single identity provider is mandatory.

- Use privacy-preserving verification (prove eligibility without exposing full identity).

3.4 Procurement & vendor capture prevention

Corporations often capture systems through contracts.

Controls:

- Open contracting: publish tender docs, bids, scoring rubrics, awarded amounts.

- Vendor rotation + caps: no vendor may exceed X% of spend for Y years.

- No proprietary lock-in: require open standards + data export + escrow for critical code.

- Independent security reviews: funded separately from project leadership.

3.5 Moderation & discourse protections (prevent censorship capture)

Moderation is where subversion hides.

Controls:

- Transparent rules + appeal process

- Independent moderation ombuds

- Public “moderation transparency reports” (volumes, reasons, outcomes)

- No private backchannels: all takedown requests must be logged (with safe redactions)

3.6 Financial integrity (anti-bribery & anti-money-influence)

Controls:

- Donation caps & disclosure (with exceptions for at-risk donors handled via blind trusts + external auditor)

- Ban “earmarked donations” that dictate policy outcomes

- Multi-sig treasury: spending requires approval from multiple independent signers (across chambers)

- Annual forensic audits by rotating audit firms + public summaries

3.7 Security model (anti-tamper, anti-insider)

- Zero-trust operations

- Immutable audit logs (tamper-evident)

- Bug bounties

- Red-team exercises (publish findings at high level)

- Whistleblower protections + anonymous reporting

4) Ownership model options (and what I recommend)

You asked “what’s the ownership?” — for anti-capture, this is the core decision.

Option 1: Intergovernmental ownership (classic UN model)

- Pros: legitimacy with states, clear treaty basis

- Cons: highest risk of state capture; slow reform

Option 2: Independent non-profit foundation (multi-stakeholder)

- Pros: more resilient; easier transparency rules; can hard-code anti-capture governance

- Cons: must work hard for global legitimacy; still funding-risk

Option 3: Federated model (recommended for resilience)

Think “Internet governance style”: a non-profit foundation maintains standards + core infrastructure, while countries/regions run compatible nodes.

- Foundation owns core protocols, reference implementations, and audit frameworks

- National/Regional nodes operate locally but must comply with constitutional standards to stay interoperable

My recommendation: Federated + Foundation

It minimizes single-point political takeover while preserving international coordination.

5) Funding: how to pay without being bought

The funding model is the #1 capture vector. The trick is diversification + caps + separation.

A. Three-bucket funding model (best practice)

- Core Integrity Fund (protected)

- pays for audits, security, oversight bodies, whistleblower program

- cannot be influenced by donors (strict firewall governance)

- Operations Fund

- platform ops, staffing, support

- funded by diversified member fees + small grants

- Program Funds

- specific initiatives (climate, education, health)

- can accept grants, but must follow anti-earmarking rules

B. Hard anti-capture funding rules

- Donor concentration cap: no donor > X% of total annual budget (e.g., 5–10%)

- No anonymous corporate funding for governance-critical functions

- Public ledger of funding sources (with protected exceptions via independent auditor)

- No “pay-to-sponsor policy”: donors cannot sponsor voting outcomes or governance changes

C. Add “citizen micro-funding” for legitimacy

Even small recurring contributions (opt-in) reduce reliance on big payers and increase democratic legitimacy.

6) Visibility: what must be public vs private

“Visibility” needs two layers: public transparency and restricted transparency (for safety/security).

Must be public (default)

- budgets + spend categories

- procurement contracts (with redactions where needed)

- meeting agendas, attendance, voting records (when safe)

- policy drafts and change logs

- audit summaries and risk registers (sanitized)

- moderation transparency reports

Must be restricted (controlled access)

- personal identity data

- security vulnerabilities before patching

- protection details for at-risk participants

- sensitive diplomatic negotiations (but publish delayed transcripts when feasible)

Key mechanism: “Transparency by design”

- Every decision generates a public receipt: what changed, who approved, which process was followed.

7) A practical “anti-capture checklist” (minimum viable defenses)

If you do nothing else, implement these 10:

- Multi-chamber governance with supermajority rule

- Independent oversight chamber with budget firewall

- Donor concentration caps + no earmarked governance funding

- Open procurement + vendor caps + no lock-in

- Tamper-evident audit logs + public decision receipts

- Transparent moderation + appeals + ombuds

- Term limits + conflict-of-interest disclosures

- Whistleblower program with legal protections

- External rotating audits + published summaries

- Federated architecture (no single host/control point)

8) RDC gap scan (5 types only)

Inference is justified here because this is high-risk governance design.

- Capability: can you staff independent audit/security and keep them independent?

- Dependency: app stores, cloud providers, payment rails, and national IDs can become choke points

- Economic: diversified funding is harder than single big donors; requires disciplined governance

- Regulatory: cross-border privacy/data sovereignty conflicts; NGO restrictions in some states

- Behavioral: trust + adoption depend on visible fairness; elites will test boundaries early

Recommendation: Test — pilot the governance + funding + audit model on a narrow domain first (e.g., climate reporting or humanitarian coordination), and measure attempted influence events.

Conclusion

The Virtual United Nations is not a replacement for existing global institutions it is their digital evolution. By integrating stakeholder-driven design, mobile-first access, social participation, and interoperability with virtual national governments, the V-UN can restore relevance, legitimacy, and effectiveness to global governance.

In an interconnected world, governance must be as digital, inclusive, and scalable as the challenges it seeks to solve.

Abbreviations & Uncertainty Tags

- V-UN: Virtual United Nations

- VNG: Virtual National Government

- RDC: Runtime Decision Core

- KK: Known Known

- KU: Known Unknown

- UU: Unknown Unknown

Final Status: Test (pilot recommended before full-scale adoption)